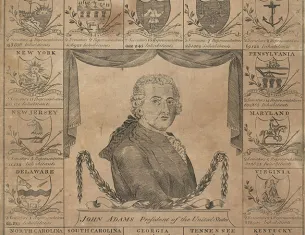

A Democratic-Republican on the Election of 1800

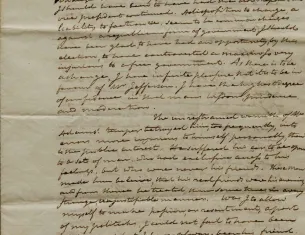

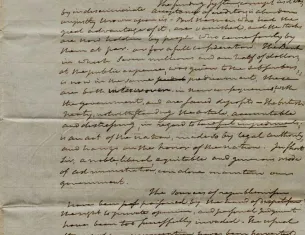

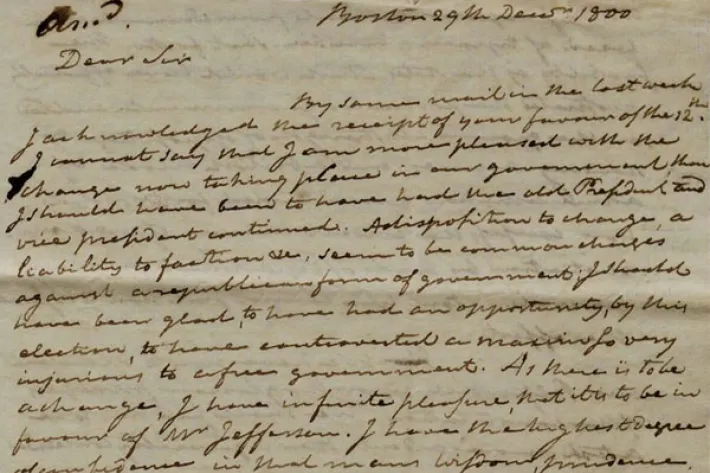

James Sullivan to John Langdon, December 29, 1800. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

The presidential election of 1800 resulted in two firsts in US history: Regardless of who would win the deadlock, Jefferson or Burr, the executive office would change parties. Many were unsure whether the nation could survive such a change. In addition, the tie for the executive office was also unprecedented, and it was unclear how the House of Representatives would deal with breaking the tie.

In this letter from December 29, 1800, James Sullivan, a Massachusetts Democratic-Republican, writes to New Hampshire senator John Langdon about the changes to come and dissects the Adams presidency.

A Letter from James Sullivan to John Langdon, December 29, 1800

Boston 29th Decer 1800

Dear Sir

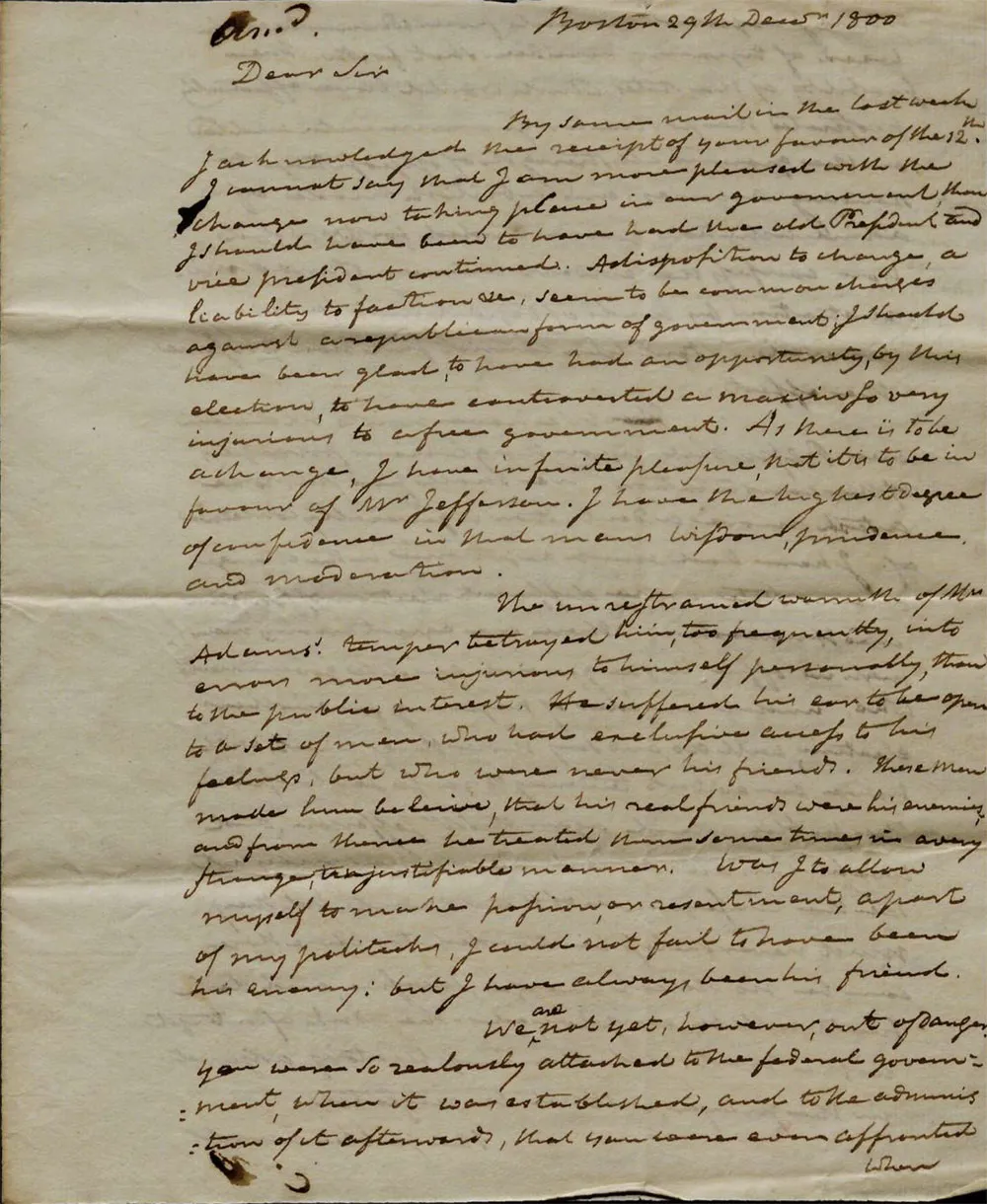

By some mail in the last week I acknowledged the receipt of your favour of the 12th. I cannot say that I am more pleased with the change now taking place in our government than I should have been to have had the old President and vice president continued. A disposition to change, a liability to faction &c, seem to be common charges against a republican form of government, I should have been glad, to have had an opportunity, by this election, to have controverted a maxim so very injurious to a free government. As there is to be a change, I have infinite pleasure, that it is to be in favour of Mr. Jefferson. I have the highest degree of confidence in that mans wisdom, prudence and moderation.

The unrestrained warmth of Mr. Adams’ temper betrayed him, too frequently, into error more injurious to himself personally, than to the public interest. He suffered his ear to be open to a set of men, who had exclusive access to his feelings, but who were never his friends. These men made him believe, that his real friends were his enemies and from thence he treated them some times in a very strange, unjustifiable manner. Was I to allow myself to make passion, or resentment, a part of my politicks, I could not fail to have been his enemy: but I have always been his friend.

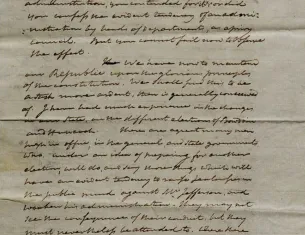

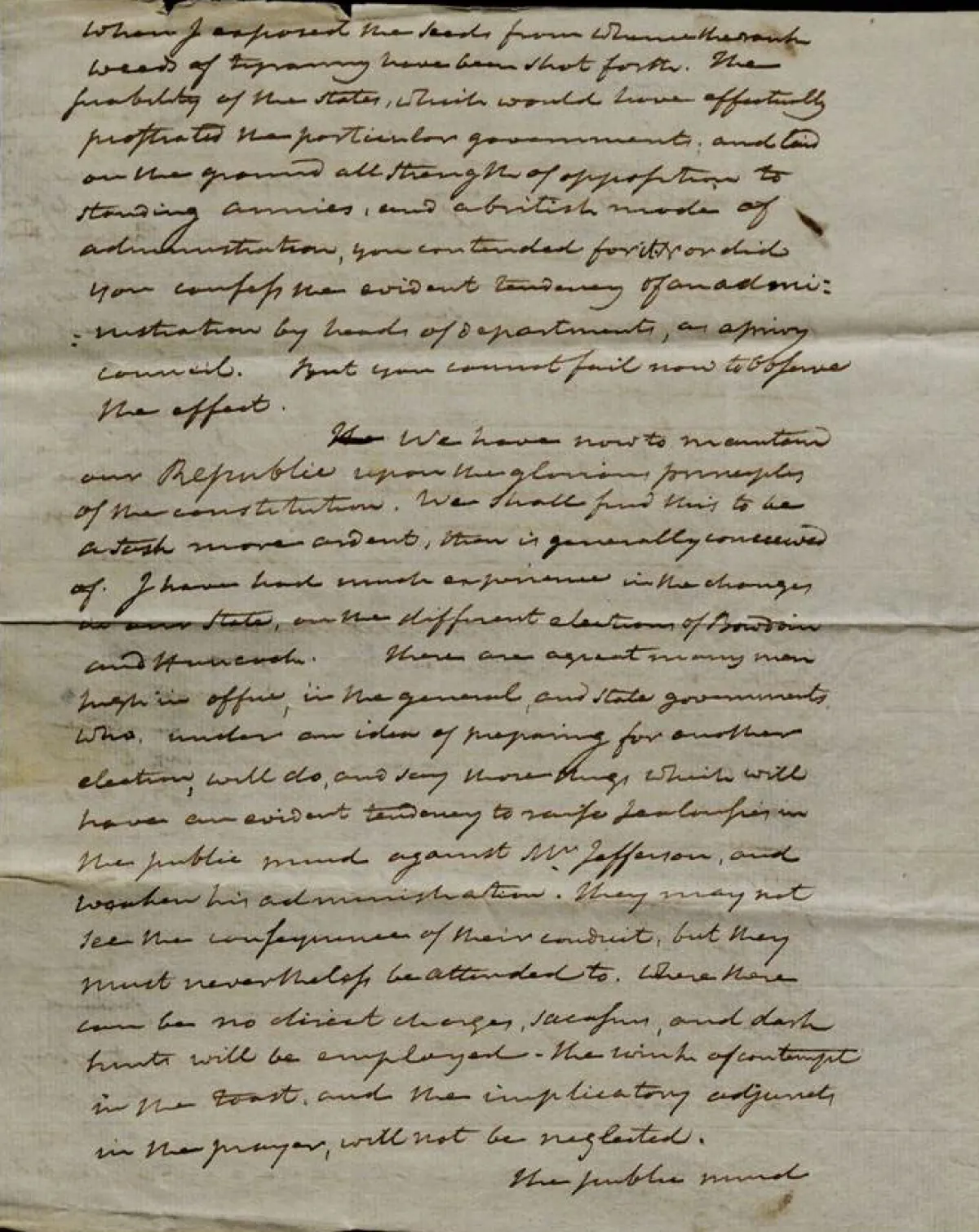

We are not yet, however, out of danger. You were so zealously attached to the federal government, when it was established, and to the administration of it afterwards, that you were even affronted when I exposed the deeds from whence the rank weeds of tyranny have been shot forth. The [Illegible] of the states, which would have effectually prostrated the particular governments, and laid on the ground all strength of opposition to standing armies, and a british mode of administration, you contended for it. Nor did you confess the evident tendency of an administration by heads of departments, as a priory council. But you cannot fail now to observe the effect.

We have now to maintain our Republic upon the glorious principles of the constitution. We shall find this to be a task more ardent, than is generally conceived of. I have had much experience in the changes in our state, on the different elections of Bowdoin and Hancock. There are a great many men high in office, in the general, and state governments who, under an idea of preparing for another election, will do, and say those things which will have an evident tendency to raise jealousies in the public mind against Mr. Jefferson, and weaken his administration. They may not see the consequence of their conduct, but they must nevertheless be attended to. Where there can be no direct charges, sarcasms, and dark hints will be employed – the wink of contempt in the toast, and the implicatory adjuncts in the prayer, will not be neglected.

The public mind must be prepared against these.

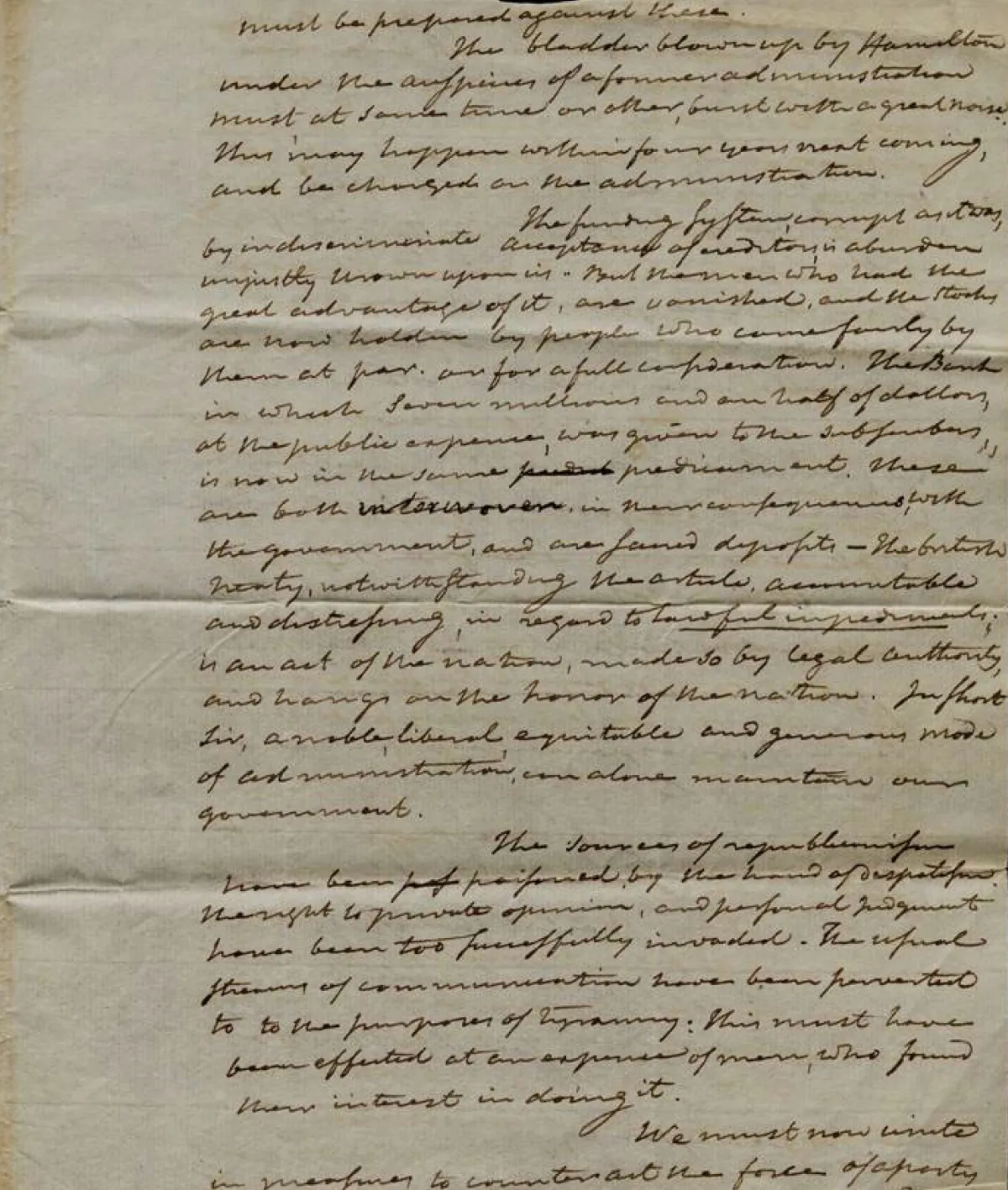

The bladder blown up by Hamilton under the auspices of a former administration must at some time or other, burst with a great noise. This may happen within four years next coming, and be charged on the administration.

The funding system, concept as it was, by indiscriminate acceptance of creditors is a burden unjustly thrown upon us. But the men who had the great advantage of it, are vanished, and the stocks are now holden by the people who came fairly by them at par or for a full cooperation. The Bank in which seven millions and an half of dollars, at the public expense, was given to the [Illegible] is now in the same predicament. These are both interwoven in their consequences, with the government, and are secured deposits. The british treaty, notwithstanding the article, accountable and distressing, in regard to lawful impediments, in an act of the nation, made so by legal authority, and hangs on the honor of the nation. In short sir, a noble liberal equitable and generous mode of administration, can alone maintain our government.

The sources of republicanism have been poisoned by the hand of despotism. The right to private opinion, and personal judgement have been too forcefully invaded. The usual streams of communication have been perverted to to the purposes of tyranny: this must have been effected at an expense of men, who found their interest in doing it.

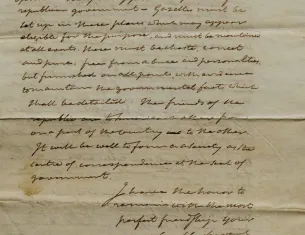

We must now unite in measures to counteract the force of a party whose restless disposition will urge them to do all within their power, to embarrass, and even to overturn the government. We must have operations formed in various parts of the nation, for communication of sentiments, by which a firm concentration of the public opinion may be supported in favour of a republican government – Gazettes must be set up in those places, which may appear eligible of the purpose, and must be maintained at all events. These must be chaste, correct and pure, free from abuse and personalities, but furnished on all points, with evidence to maintain the governmental facts which shall be detailed. The friends of the republic are to know each other from one part of the country to the other. It will be well to form a [Illegible] as the centre of correspondence at the seat of government.

I have the honor to

remain with the most

perfect friendship your

most humble servant

Ja Sullivan

Honble

John Langdon Esq

Source: James Sullivan to John Langdon, December 29, 1800, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC06535.

A Letter from James Sullivan to John Langdon, December 29, 1800

Boston 29th Decer 1800

Dear Sir

. . . I cannot say that I am more pleased with the change now taking place in our government than I should have been to have had the old President and vice president continued. . . . I should have been glad, to have had an opportunity, by this election, to have controverted a maxim so very injurious to a free government. As there is to be a change, I have infinite pleasure, that it is to be in favour of Mr. Jefferson. I have the highest degree of confidence in that mans wisdom, prudence and moderation.

The unrestrained warmth of Mr. Adams’ temper betrayed him, too frequently, into error more injurious to himself personally, than to the public interest. He suffered his ear to be open to a set of men, who had exclusive access to his feelings, but who were never his friends. These men made him believe, that his real friends were his enemies and from thence he treated them some times in a very strange, unjustifiable manner . . .

We are not yet, however, out of danger . . .

We have now to maintain our Republic upon the glorious principles of the constitution. We shall find this to be a task more ardent, than is generally conceived of. . . . which will have an evident tendency to raise jealousies in the public mind against Mr. Jefferson, and weaken his administration . . .

The public mind must be prepared against these.

The bladder blown up by Hamilton under the auspices of a former administration must at some time or other, burst with a great noise. This may happen within four years next coming, and be charged on the administration . . .

The sources of republicanism have been poisoned by the hand of despotism. The right to private opinion, and personal judgement have been too forcefully invaded. The usual streams of communication have been perverted to to the purposes of tyranny . . .

We must now unite in measures to counteract the force of a party whose restless disposition will urge them to do all within their power, to embarrass, and even to overturn the government . . . These must be chaste, correct and pure, free from abuse and personalities, but furnished on all points, with evidence to maintain the governmental facts which shall be detailed. The friends of the republic are to know each other from one part of the country to the other . . .

I have the honor to

remain with the most

perfect friendship your

most humble servant

Ja Sullivan

Source: James Sullivan to John Langdon, December 29, 1800, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC06535.

maxim - principle or rule of conduct

thence - that reason

ardent - burning, important

perverted - distorted

tyranny - harsh, unjust exercise of government power

chaste - stainless

Background

The presidential election of 1800 resulted in two firsts in US history: Regardless of who would win the deadlock, Jefferson or Burr, the executive office would change parties. Many were unsure whether the nation could survive such a change. In addition, the tie for the executive office was also unprecedented, and it was unclear how the House of Representatives would deal with breaking the tie.

In this letter from December 29, 1800, James Sullivan, a Massachusetts Democratic-Republican, writes to New Hampshire senator John Langdon about the changes to come and dissects the Adams presidency.

Transcript

A Letter from James Sullivan to John Langdon, December 29, 1800

Boston 29th Decer 1800

Dear Sir

By some mail in the last week I acknowledged the receipt of your favour of the 12th. I cannot say that I am more pleased with the change now taking place in our government than I should have been to have had the old President and vice president continued. A disposition to change, a liability to faction &c, seem to be common charges against a republican form of government, I should have been glad, to have had an opportunity, by this election, to have controverted a maxim so very injurious to a free government. As there is to be a change, I have infinite pleasure, that it is to be in favour of Mr. Jefferson. I have the highest degree of confidence in that mans wisdom, prudence and moderation.

The unrestrained warmth of Mr. Adams’ temper betrayed him, too frequently, into error more injurious to himself personally, than to the public interest. He suffered his ear to be open to a set of men, who had exclusive access to his feelings, but who were never his friends. These men made him believe, that his real friends were his enemies and from thence he treated them some times in a very strange, unjustifiable manner. Was I to allow myself to make passion, or resentment, a part of my politicks, I could not fail to have been his enemy: but I have always been his friend.

We are not yet, however, out of danger. You were so zealously attached to the federal government, when it was established, and to the administration of it afterwards, that you were even affronted when I exposed the deeds from whence the rank weeds of tyranny have been shot forth. The [Illegible] of the states, which would have effectually prostrated the particular governments, and laid on the ground all strength of opposition to standing armies, and a british mode of administration, you contended for it. Nor did you confess the evident tendency of an administration by heads of departments, as a priory council. But you cannot fail now to observe the effect.

We have now to maintain our Republic upon the glorious principles of the constitution. We shall find this to be a task more ardent, than is generally conceived of. I have had much experience in the changes in our state, on the different elections of Bowdoin and Hancock. There are a great many men high in office, in the general, and state governments who, under an idea of preparing for another election, will do, and say those things which will have an evident tendency to raise jealousies in the public mind against Mr. Jefferson, and weaken his administration. They may not see the consequence of their conduct, but they must nevertheless be attended to. Where there can be no direct charges, sarcasms, and dark hints will be employed – the wink of contempt in the toast, and the implicatory adjuncts in the prayer, will not be neglected.

The public mind must be prepared against these.

The bladder blown up by Hamilton under the auspices of a former administration must at some time or other, burst with a great noise. This may happen within four years next coming, and be charged on the administration.

The funding system, concept as it was, by indiscriminate acceptance of creditors is a burden unjustly thrown upon us. But the men who had the great advantage of it, are vanished, and the stocks are now holden by the people who came fairly by them at par or for a full cooperation. The Bank in which seven millions and an half of dollars, at the public expense, was given to the [Illegible] is now in the same predicament. These are both interwoven in their consequences, with the government, and are secured deposits. The british treaty, notwithstanding the article, accountable and distressing, in regard to lawful impediments, in an act of the nation, made so by legal authority, and hangs on the honor of the nation. In short sir, a noble liberal equitable and generous mode of administration, can alone maintain our government.

The sources of republicanism have been poisoned by the hand of despotism. The right to private opinion, and personal judgement have been too forcefully invaded. The usual streams of communication have been perverted to to the purposes of tyranny: this must have been effected at an expense of men, who found their interest in doing it.

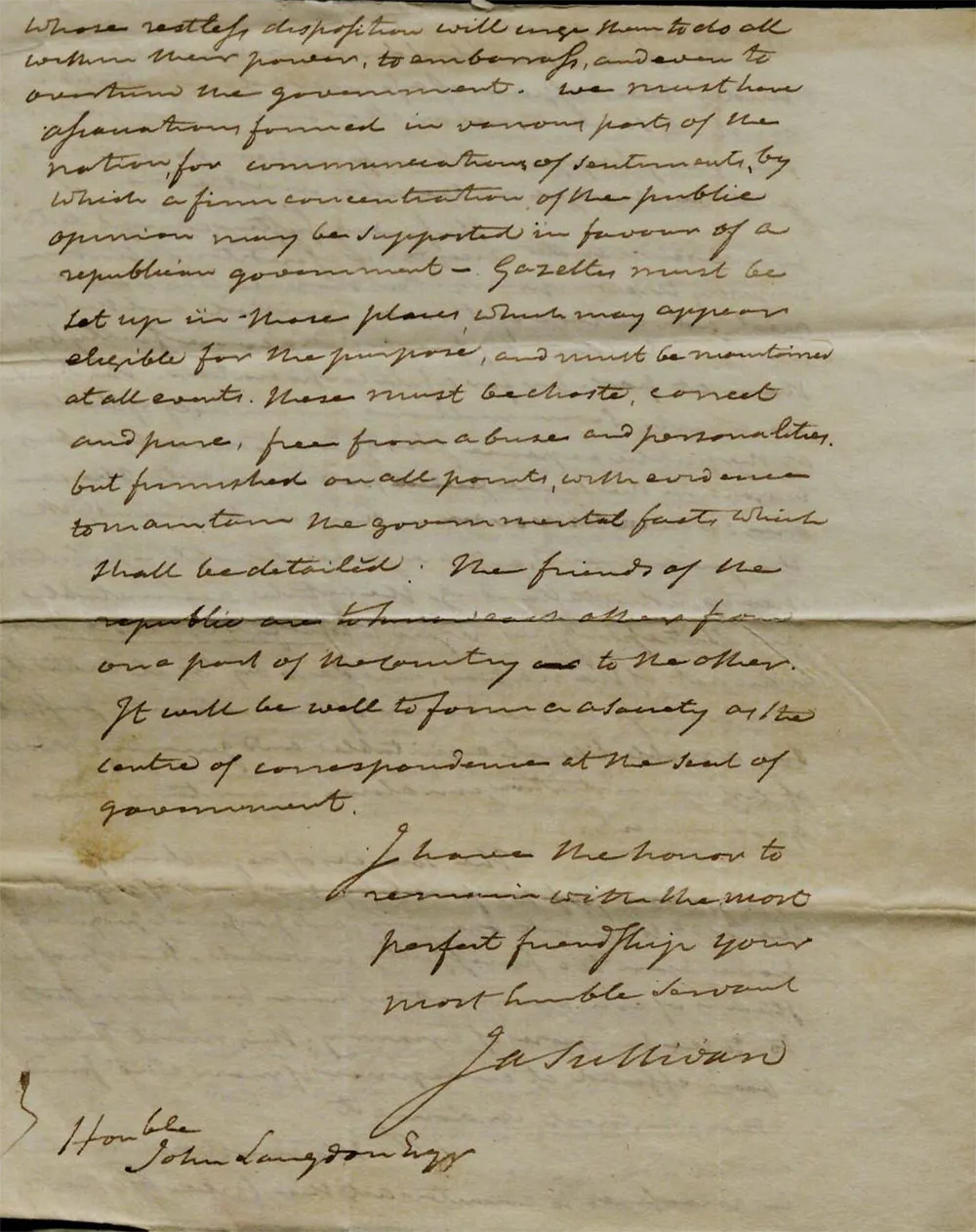

We must now unite in measures to counteract the force of a party whose restless disposition will urge them to do all within their power, to embarrass, and even to overturn the government. We must have operations formed in various parts of the nation, for communication of sentiments, by which a firm concentration of the public opinion may be supported in favour of a republican government – Gazettes must be set up in those places, which may appear eligible of the purpose, and must be maintained at all events. These must be chaste, correct and pure, free from abuse and personalities, but furnished on all points, with evidence to maintain the governmental facts which shall be detailed. The friends of the republic are to know each other from one part of the country to the other. It will be well to form a [Illegible] as the centre of correspondence at the seat of government.

I have the honor to

remain with the most

perfect friendship your

most humble servant

Ja Sullivan

Honble

John Langdon Esq

Source: James Sullivan to John Langdon, December 29, 1800, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC06535.

Excerpt

A Letter from James Sullivan to John Langdon, December 29, 1800

Boston 29th Decer 1800

Dear Sir

. . . I cannot say that I am more pleased with the change now taking place in our government than I should have been to have had the old President and vice president continued. . . . I should have been glad, to have had an opportunity, by this election, to have controverted a maxim so very injurious to a free government. As there is to be a change, I have infinite pleasure, that it is to be in favour of Mr. Jefferson. I have the highest degree of confidence in that mans wisdom, prudence and moderation.

The unrestrained warmth of Mr. Adams’ temper betrayed him, too frequently, into error more injurious to himself personally, than to the public interest. He suffered his ear to be open to a set of men, who had exclusive access to his feelings, but who were never his friends. These men made him believe, that his real friends were his enemies and from thence he treated them some times in a very strange, unjustifiable manner . . .

We are not yet, however, out of danger . . .

We have now to maintain our Republic upon the glorious principles of the constitution. We shall find this to be a task more ardent, than is generally conceived of. . . . which will have an evident tendency to raise jealousies in the public mind against Mr. Jefferson, and weaken his administration . . .

The public mind must be prepared against these.

The bladder blown up by Hamilton under the auspices of a former administration must at some time or other, burst with a great noise. This may happen within four years next coming, and be charged on the administration . . .

The sources of republicanism have been poisoned by the hand of despotism. The right to private opinion, and personal judgement have been too forcefully invaded. The usual streams of communication have been perverted to to the purposes of tyranny . . .

We must now unite in measures to counteract the force of a party whose restless disposition will urge them to do all within their power, to embarrass, and even to overturn the government . . . These must be chaste, correct and pure, free from abuse and personalities, but furnished on all points, with evidence to maintain the governmental facts which shall be detailed. The friends of the republic are to know each other from one part of the country to the other . . .

I have the honor to

remain with the most

perfect friendship your

most humble servant

Ja Sullivan

Source: James Sullivan to John Langdon, December 29, 1800, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC06535.

maxim - principle or rule of conduct

thence - that reason

ardent - burning, important

perverted - distorted

tyranny - harsh, unjust exercise of government power

chaste - stainless