An Address to the People of Great Britain, 1774

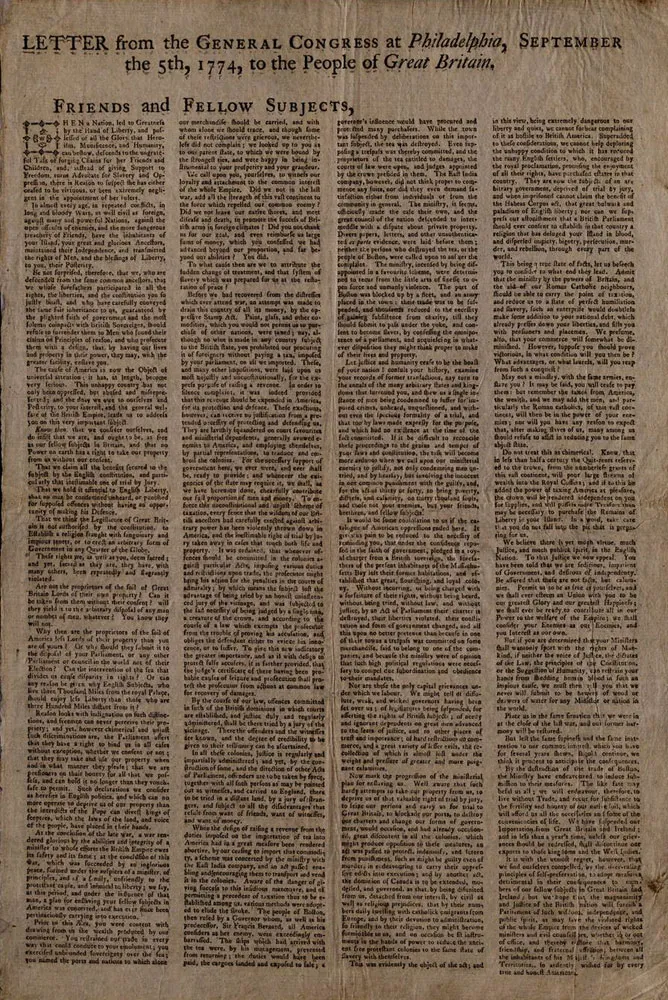

The General Congress at Philadelphia, September 5, 1774. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

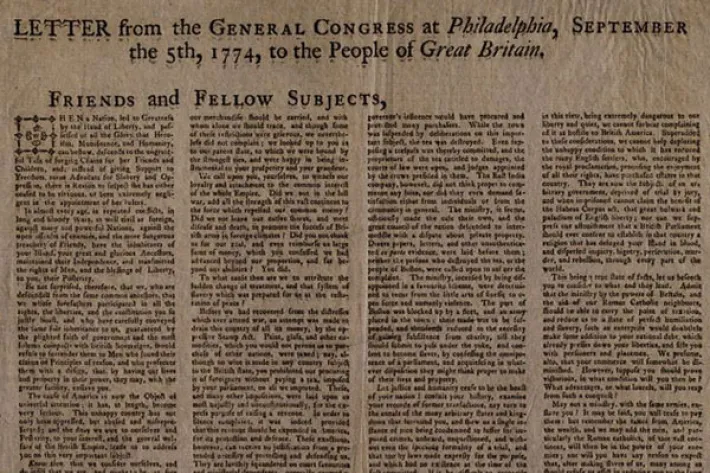

This long broadside, written by the First Continental Congress on September 5, 1774, was addressed to the people of Great Britain. It was probably printed in England and addressed the English public as “friends and fellow subjects.”

Excerpts from a Letter from the General Congress to the People of Great Britain, September 5, 1774

Friends and Fellow Subjects,

When a Nation, led to Greatness by the Hand of Liberty, and possessed of all the Glory that Heroism, Munificence, and Humanity, can bestow, descends to the ungrateful Talk of forging Chains for her Friends and Children, and, instead of giving Support to Freedom, turns Advocate for Slavery and Oppression, there is Reason to suspect she has either ceased to be virtuous, or been extremely negligent in the appointment of her rulers . . .

At the conclusion of the late war, . . . under the influence of that man, a plan for enslaving your fellow subjects in America was concerted, and has ever since been pertinaciously carrying into execution.

Prior to this Era, you were content with drawing from us the wealth produced by our commerce. You strained our trade in every way that could conduce to your emolument; you exercised unbounded sovereignty over the sea; you named the ports and nations to which alone our merchandise should be carried, and with whom alone we should trade, and though some of these restrictions were grievous, we nevertheless did not complain; we looked up to you as to our parent state, to which we were bound by the strongest ties, and were happy in being instrumental to your prosperity and your grandeur . . .

Before we had recovered from the distresses which ever attend war, an attempt was made to drain this country of all its money, by the oppressive Stamp Act. Paint, glass, and other commodities, which you would not permit us to purchase of other nations, were taxed; nay, although no wine is made in any country subject to the British state, you prohibited our procuring it of foreigners without paying a tax, imposed by your parliament, on all we imported. These, and many other impositions, were laid upon us most unjustly and unconstitutionally, for the express purpose of raising a revenue. In order to silence complaint, it was indeed provided that this revenue should be expended in America, for its protection and defence. These exactions, however, can receive no justification from a pretended necessity of protecting and defending us. They were lavishly squandered on court favourites and ministerial dependents, generally avowed enemies to America . . . To enforce this unconstitutional and unjust scheme of taxation, every fence that the wisdom of our British ancestors had carefully erected against arbitrary power has been violently thrown down in America, and the inestimable right of trial by jury taken away in cases that touch both life and property . . .

Nor are these the only capital grievances under which we labour. We might tell of dissolute, weak, and wicked governors having been set over us; of legislatures being suspended for asserting the rights of British subjects; of needy and ignorant dependents on great men advanced to the seats of justice, and to other places of trust and importance; of hard restrictions on commerce, and a great variety of lesser evils . . .

Now mark the progression of the ministerial plan for enslaving us. Well aware that such hardy attempts to take our property from us, to deprive us of that valuable right of trial by jury, to seize our persons and carry us for trial to Great Britain, to blockade our ports, to destroy our charters, and change our forms of government, would occasion, and had already occasioned, great discontent in all the colonies, which might produce opposition to these measures, an act was passed to protect, indemnify, and screen from punishment, such as might be guilty even of murder, in endeavouring to carry their oppressive edicts into execution; and by another act, the dominion of Canada is to be extended, modelled, and governed, as that by being disunited from us, detached from our interest, by civil as well as religious prejudices, that by their numbers daily swelling with catholick emigrants from Europe, and by their devotion to administration, so friendly to their religion, they might become formidable to us, and on occasion, be fit instruments in the hands of power to reduce the ancient free protestant colonies to the same state of slavery with themselves . . .

May not a ministry, with the same armies, enslave you? It may be said, you will cease to pay them: but remember the taxes from America, the wealth, and we may add the men and particularly the Roman catholics, of this vast continent, will then be in the power of your enemies; nor will you have any reason to expect that, after making slaves of us, many among us should refuse to assist in reducing you to the same abject state . . .

Source: Letter from the General Congress to the People of Great Britain, September 5, 1774, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC04774.

Letter from the General Congress to the People of Great Britain, September 5, 1774

Friends and Fellow Subjects,

When a Nation, led to Greatness by the Hand of Liberty, and possessed of all the Glory that Heroism, Munificence, and Humanity, can bestow, descends to the ungrateful Talk of forging Chains for her Friends and Children, and, instead of giving Support to Freedom, turns Advocate for Slavery and Oppression, there is Reason to suspect she has either ceased to be virtuous, or been extremely negligent in the appointment of her rulers . . .

At the conclusion of the late war, . . . under the influence of that man, a plan for enslaving your fellow subjects in America was concerted . . .

Before we had recovered from the distresses which ever attend war, an attempt was made to drain this country of all its money by the oppressive Stamp Act. Paint, glass, and other commodities, which you would not permit us to purchase of other nations, were taxed; nay, although no wine is made in any country subject to the British state, you prohibited our procuring it of foreigners without paying a tax . . .

Now mark the progression of the ministerial plan for enslaving us. Well aware that such hardy attempts to take our property from us, to deprive us of that valuable right of trial by jury, to seize our persons and carry us for trial to Great Britain, to blockade our ports, to destroy our charters, and change our forms of government . . .

May not a ministry, with the same armies, enslave you? It may be said, you will cease to pay them: but remember the taxes from America, the wealth, and we may add the men and particularly the Roman catholics, of this vast continent, will then be in the power of your enemies; nor will you have any reason to expect that, after making slaves of us, many among us should refuse to assist in reducing you to the same abject state . . .

Source: Letter from the General Congress to the People of Great Britain, September 5, 1774, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC04774.

Munificence - great generosity

commodities - raw materials

procuring - obtaining

Background

This long broadside, written by the First Continental Congress on September 5, 1774, was addressed to the people of Great Britain. It was probably printed in England and addressed the English public as “friends and fellow subjects.”

Transcript

Excerpts from a Letter from the General Congress to the People of Great Britain, September 5, 1774

Friends and Fellow Subjects,

When a Nation, led to Greatness by the Hand of Liberty, and possessed of all the Glory that Heroism, Munificence, and Humanity, can bestow, descends to the ungrateful Talk of forging Chains for her Friends and Children, and, instead of giving Support to Freedom, turns Advocate for Slavery and Oppression, there is Reason to suspect she has either ceased to be virtuous, or been extremely negligent in the appointment of her rulers . . .

At the conclusion of the late war, . . . under the influence of that man, a plan for enslaving your fellow subjects in America was concerted, and has ever since been pertinaciously carrying into execution.

Prior to this Era, you were content with drawing from us the wealth produced by our commerce. You strained our trade in every way that could conduce to your emolument; you exercised unbounded sovereignty over the sea; you named the ports and nations to which alone our merchandise should be carried, and with whom alone we should trade, and though some of these restrictions were grievous, we nevertheless did not complain; we looked up to you as to our parent state, to which we were bound by the strongest ties, and were happy in being instrumental to your prosperity and your grandeur . . .

Before we had recovered from the distresses which ever attend war, an attempt was made to drain this country of all its money, by the oppressive Stamp Act. Paint, glass, and other commodities, which you would not permit us to purchase of other nations, were taxed; nay, although no wine is made in any country subject to the British state, you prohibited our procuring it of foreigners without paying a tax, imposed by your parliament, on all we imported. These, and many other impositions, were laid upon us most unjustly and unconstitutionally, for the express purpose of raising a revenue. In order to silence complaint, it was indeed provided that this revenue should be expended in America, for its protection and defence. These exactions, however, can receive no justification from a pretended necessity of protecting and defending us. They were lavishly squandered on court favourites and ministerial dependents, generally avowed enemies to America . . . To enforce this unconstitutional and unjust scheme of taxation, every fence that the wisdom of our British ancestors had carefully erected against arbitrary power has been violently thrown down in America, and the inestimable right of trial by jury taken away in cases that touch both life and property . . .

Nor are these the only capital grievances under which we labour. We might tell of dissolute, weak, and wicked governors having been set over us; of legislatures being suspended for asserting the rights of British subjects; of needy and ignorant dependents on great men advanced to the seats of justice, and to other places of trust and importance; of hard restrictions on commerce, and a great variety of lesser evils . . .

Now mark the progression of the ministerial plan for enslaving us. Well aware that such hardy attempts to take our property from us, to deprive us of that valuable right of trial by jury, to seize our persons and carry us for trial to Great Britain, to blockade our ports, to destroy our charters, and change our forms of government, would occasion, and had already occasioned, great discontent in all the colonies, which might produce opposition to these measures, an act was passed to protect, indemnify, and screen from punishment, such as might be guilty even of murder, in endeavouring to carry their oppressive edicts into execution; and by another act, the dominion of Canada is to be extended, modelled, and governed, as that by being disunited from us, detached from our interest, by civil as well as religious prejudices, that by their numbers daily swelling with catholick emigrants from Europe, and by their devotion to administration, so friendly to their religion, they might become formidable to us, and on occasion, be fit instruments in the hands of power to reduce the ancient free protestant colonies to the same state of slavery with themselves . . .

May not a ministry, with the same armies, enslave you? It may be said, you will cease to pay them: but remember the taxes from America, the wealth, and we may add the men and particularly the Roman catholics, of this vast continent, will then be in the power of your enemies; nor will you have any reason to expect that, after making slaves of us, many among us should refuse to assist in reducing you to the same abject state . . .

Source: Letter from the General Congress to the People of Great Britain, September 5, 1774, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC04774.

Excerpt

Letter from the General Congress to the People of Great Britain, September 5, 1774

Friends and Fellow Subjects,

When a Nation, led to Greatness by the Hand of Liberty, and possessed of all the Glory that Heroism, Munificence, and Humanity, can bestow, descends to the ungrateful Talk of forging Chains for her Friends and Children, and, instead of giving Support to Freedom, turns Advocate for Slavery and Oppression, there is Reason to suspect she has either ceased to be virtuous, or been extremely negligent in the appointment of her rulers . . .

At the conclusion of the late war, . . . under the influence of that man, a plan for enslaving your fellow subjects in America was concerted . . .

Before we had recovered from the distresses which ever attend war, an attempt was made to drain this country of all its money by the oppressive Stamp Act. Paint, glass, and other commodities, which you would not permit us to purchase of other nations, were taxed; nay, although no wine is made in any country subject to the British state, you prohibited our procuring it of foreigners without paying a tax . . .

Now mark the progression of the ministerial plan for enslaving us. Well aware that such hardy attempts to take our property from us, to deprive us of that valuable right of trial by jury, to seize our persons and carry us for trial to Great Britain, to blockade our ports, to destroy our charters, and change our forms of government . . .

May not a ministry, with the same armies, enslave you? It may be said, you will cease to pay them: but remember the taxes from America, the wealth, and we may add the men and particularly the Roman catholics, of this vast continent, will then be in the power of your enemies; nor will you have any reason to expect that, after making slaves of us, many among us should refuse to assist in reducing you to the same abject state . . .

Source: Letter from the General Congress to the People of Great Britain, September 5, 1774, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC04774.

Munificence - great generosity

commodities - raw materials

procuring - obtaining