Theodosia Burr Alston to Albert Gallatin on Her Father’s Exile, 1811

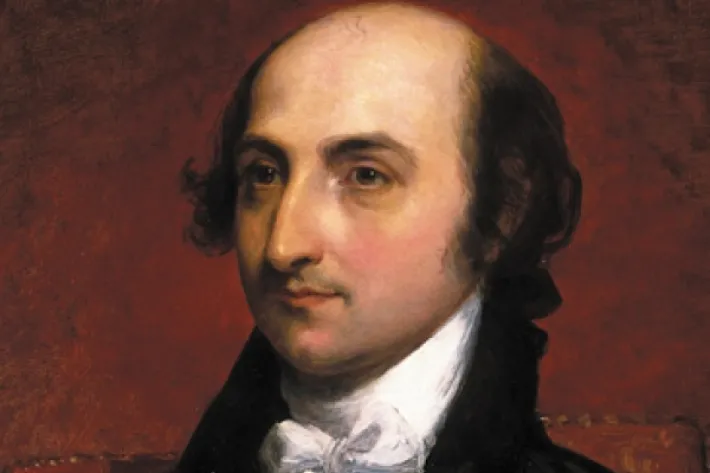

Albert Gallatin, by Thomas Worthington Whittredge after Gilbert Stuart, ca.1859. (National Portrait Gallery)

In 1807 Aaron Burr, former vice president of the United States, was accused of plotting to establish a separate country in the West on land claimed by the United States and Spain. He was charged with treason, but was acquitted for lack of evidence. In disgrace and in fear for his life, he left for Europe. His daughter, Theodosia Alston, wrote letters to political leaders in an effort to secure a smooth return for her father. This letter to Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin on March 9, 1811, seeks his opinion on what her father would face if he returned to the United States. After four years in exile, Aaron Burr returned to America in mid-1812. The United States was on the brink of war with Britain and the Burr Conspiracy seemed ancient history.

A Letter from Theodosia Burr Alston to Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin, March 9, 1811

March 9, 1811

Though convinced of your firmness, still with the utmost diffidence I venture to address you on a subject which it is almost dangerous to mention, and which, in itself, affords me no claim on your attention. Yet, trusting that you will not withhold an opinion deeply interesting to me, and which your present station enables you to form with peculiar correctness, I venture to inquire whether you suppose that my father's return to this country would be productive of ill consequences to him, or draw on him farther prosecution from any branch of the government.

You will the more readily forgive me for taking the liberty to make such a request, when you reflect that, retired as I am from the world, it is impossible for me to gather the general opinion from my own observation. I am, indeed, perfectly aware how unexpected will be this demand; that it places you in a situation of some delicacy; and that to return a satisfactory answer will be to exert liberality and candour; I am aware of all this, and yet do not desist.

Recollect what are my incitements. Recollect that I have seen my father dashed from the high rank he held in the minds of his country-men, imprisoned, and forced into exile. Must he ever remain thus excommunicated from the participation of domestic enjoyments and the privileges of a citizen; aloof from his accustomed sphere, and singled, out as a mark for the shafts of calumny ? Why should he be thus proscribed and held up in execration ? What benefit to the country can possibly accrue from the continuation of this system? Surely it must be evident to the worst enemies of my father, that no man, situated as he will be, could obtain any undue influence, even supposing him desirous of it.

But pardon me if my feeling has led me astray from my object, which was not to enter upon a discussion with you. I seek only to solicit an enlightened opinion relative to facts which involve my best hopes of happiness.

Present, if you please, my respects to Mrs. Gallatin, and accept the assurances of my high consideration.

Theo. Burr Alston

Source: Theodosia Burr Alston to Albert Gallatin, March 9, 1811, The Private Journal of Aaron Burr during His Residence of Four Years in Europe with Selections from His Correspondence, vol. 2, ed. Matthew Davis (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1858), pp. 155–156.

A Letter from Theodosia Burr Alston to Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin, March 9, 1811

March 9, 1811

Though convinced of your firmness, still with the utmost diffidence I venture to address you on a subject which it is almost dangerous to mention, and which, in itself, affords me no claim on your attention . . . I venture to inquire whether you suppose that my father’s return to this country would be productive of ill consequences to him, or draw on him farther prosecution from any branch of the government.

You will the more readily forgive me for taking the liberty to make such a request, when you reflect that, retired as I am from the world, it is impossible for me to gather the general opinion from my own observation . . . Recollect that I have seen my father dashed from the high rank he held in the minds of his country– men, imprisoned, and forced into exile. Must he ever remain thus excommunicated from the participation of domestic enjoyments and the privileges of a citizen? . . . Surely it must be evident to the worst enemies of my father, that no man, situated as he will be, could obtain any undue influence, even supposing him desirous of it. But pardon me if my feeling has led me astray from my object, which was not to enter upon a discussion with you. I seek only to solicit an enlightened opinion relative to facts which involve my best hopes of happiness.

Present, if you please, my respects to Mrs. Gallatin, and accept the assurances of my high consideration.

Theo. Burr Alston

Source: Theodosia Burr Alston to Albert Gallatin, March 9, 1811, The Private Journal of Aaron Burr during His Residence of Four Years in Europe with Selections from His Correspondence, vol. 2, ed. Matthew Davis (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1858), pp. 155–156.

Background

In 1807 Aaron Burr, former vice president of the United States, was accused of plotting to establish a separate country in the West on land claimed by the United States and Spain. He was charged with treason, but was acquitted for lack of evidence. In disgrace and in fear for his life, he left for Europe. His daughter, Theodosia Alston, wrote letters to political leaders in an effort to secure a smooth return for her father. This letter to Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin on March 9, 1811, seeks his opinion on what her father would face if he returned to the United States. After four years in exile, Aaron Burr returned to America in mid-1812. The United States was on the brink of war with Britain and the Burr Conspiracy seemed ancient history.

Transcript

A Letter from Theodosia Burr Alston to Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin, March 9, 1811

March 9, 1811

Though convinced of your firmness, still with the utmost diffidence I venture to address you on a subject which it is almost dangerous to mention, and which, in itself, affords me no claim on your attention. Yet, trusting that you will not withhold an opinion deeply interesting to me, and which your present station enables you to form with peculiar correctness, I venture to inquire whether you suppose that my father's return to this country would be productive of ill consequences to him, or draw on him farther prosecution from any branch of the government.

You will the more readily forgive me for taking the liberty to make such a request, when you reflect that, retired as I am from the world, it is impossible for me to gather the general opinion from my own observation. I am, indeed, perfectly aware how unexpected will be this demand; that it places you in a situation of some delicacy; and that to return a satisfactory answer will be to exert liberality and candour; I am aware of all this, and yet do not desist.

Recollect what are my incitements. Recollect that I have seen my father dashed from the high rank he held in the minds of his country-men, imprisoned, and forced into exile. Must he ever remain thus excommunicated from the participation of domestic enjoyments and the privileges of a citizen; aloof from his accustomed sphere, and singled, out as a mark for the shafts of calumny ? Why should he be thus proscribed and held up in execration ? What benefit to the country can possibly accrue from the continuation of this system? Surely it must be evident to the worst enemies of my father, that no man, situated as he will be, could obtain any undue influence, even supposing him desirous of it.

But pardon me if my feeling has led me astray from my object, which was not to enter upon a discussion with you. I seek only to solicit an enlightened opinion relative to facts which involve my best hopes of happiness.

Present, if you please, my respects to Mrs. Gallatin, and accept the assurances of my high consideration.

Theo. Burr Alston

Source: Theodosia Burr Alston to Albert Gallatin, March 9, 1811, The Private Journal of Aaron Burr during His Residence of Four Years in Europe with Selections from His Correspondence, vol. 2, ed. Matthew Davis (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1858), pp. 155–156.

Excerpt

A Letter from Theodosia Burr Alston to Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin, March 9, 1811

March 9, 1811

Though convinced of your firmness, still with the utmost diffidence I venture to address you on a subject which it is almost dangerous to mention, and which, in itself, affords me no claim on your attention . . . I venture to inquire whether you suppose that my father’s return to this country would be productive of ill consequences to him, or draw on him farther prosecution from any branch of the government.

You will the more readily forgive me for taking the liberty to make such a request, when you reflect that, retired as I am from the world, it is impossible for me to gather the general opinion from my own observation . . . Recollect that I have seen my father dashed from the high rank he held in the minds of his country– men, imprisoned, and forced into exile. Must he ever remain thus excommunicated from the participation of domestic enjoyments and the privileges of a citizen? . . . Surely it must be evident to the worst enemies of my father, that no man, situated as he will be, could obtain any undue influence, even supposing him desirous of it. But pardon me if my feeling has led me astray from my object, which was not to enter upon a discussion with you. I seek only to solicit an enlightened opinion relative to facts which involve my best hopes of happiness.

Present, if you please, my respects to Mrs. Gallatin, and accept the assurances of my high consideration.

Theo. Burr Alston

Source: Theodosia Burr Alston to Albert Gallatin, March 9, 1811, The Private Journal of Aaron Burr during His Residence of Four Years in Europe with Selections from His Correspondence, vol. 2, ed. Matthew Davis (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1858), pp. 155–156.