Petition to Protect Freed Slaves, 1797

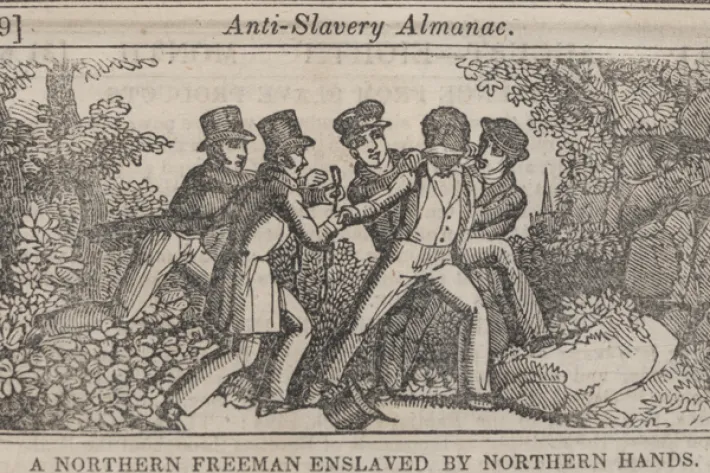

The American Anti-Slavery Almanac for 1839, vol. 1, no. 4 (New York, 1839), p. 19. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

In response to a North Carolina law that legalized the capture and reenslavement of emancipated people, Absalom Jones drafted a petition to the US Congress on behalf of four recently freed men living in Philadelphia. The petitioners implored Congress to end this treacherous practice, which, they argued, was in direct violation of the Constitution.

Petition drafted by Absalom Jones and submitted to the United States Congress by

Jacob Nicholson, Jupiter Nicholson, Job Albert, and Thomas Pritchet, January 23, 1797

To the President, Senate, and House of Representatives.

The PETITION and REPRESENTATION of the undernamed FREEMEN,

Respectfully Sheweth:

THAT being of African descent, late inhabitants and natives of North Carolina, to you only, under God, can we apply with any hope of effect, for redress of our grievances, having been compelled to leave the state wherein we had a right of residence, as freemen liberated under the hand and seal of humane and conscientious masters, the validity of which act of justice, in restoring us to our native right of freedom, was confirmed by judgment of the Superior court of North-Carolina, wherein it was brought to trial; yet not long after this decision, a law of that state was enacted, under which men of cruel disposition, and void of just principle, received countenance and authority in violently seizing, imprisoning and selling into slavery, such as had been so emancipated; whereby we were reduced to the necessity of separating from some of our nearest and most tender connections, and of seeking refuge in such parts of the Union where more regard is paid to the public declaration in favour of liberty and the common right of men, several hundreds under our circumstance having, in consequence of the said law, been hunted day and night, like beasts of the forest, by armed men with dogs, and made prey of as free and lawful plunder. Among others thus exposed, I Jupiter Nicholson, or Perquimons county, North-Carolina, after being set free by my master, Thomas Nicholson, and having been about two years employed as a seaman in the service of Zachary Nickson, on coming on shore, was pursued by men with dog and arms; but was favoured to escape by night to Virginia, with my wife, who was manumited by Gabriel Cosand, where I resided about four years in the town of Portsmouth, chiefly employed in sawing boards and scantling; from thence I removed with my wife to Philadelphia, where I have been employed at times by water, working along shore, or sawing wood. I left behind me a father and mother, who were manumitted by Thomas Nicholson and Zachary Dickson; they have been since taken up with a beloved brother, and sold into cruel bondage.

I Jacob Nicholson, also of North Carolina, being set free by my master, Joseph Nicholson, but continuing to live with him till being pursued day and night I was obliged to leave my abode, sleep in the woods, and stacks in the fields, &c. to escape the hands of violent men, who, induced by the profit afforded them by law, followed this course as a business; at length by night I made my escape, leaving a mother, one child and two brothers, to see whom I dare not return.

I Job Albert, manumitted by Benjamin Albertson, who was my careful guardian to protect me from being afterwards taken and sold, providing me with a house to accommodate me and my wife, who was liberated by William Robertson; but we were night and day hunted by men armed with guns, swords and pistols, accompanied with mastiff dogs; from whose violence being one night apprehensive of immediate danger, I left my dwelling locked and barred and fastened with a chain, lying at some distance from it, while my wife was by my kind master locked up under his roof; I heard them break into my house, where not finding their prey, they got but a small booty, a handkerchief of about a dollar value, and some provisions; but not long after I was discovered and seized by Alexander Stafford, William Stafford and Thomas Creesy, who were armed with guns and clubs: after binding me with my hands behind me, and a rope round my arms and body, they took me about four miles to Hartford prison, where I lay four weeks, suffering much for want of provision; from thence, with the assistance of a fellow-prisoner, a white man, I made my escape, and for three dollars was conveyed with my wife by a humane person, in a covered waggon by night, to Virginia, where, in the neighborhood of Portsmouth, I continued unmolested about four years, being chiefly engaged in sawing boards and blank. On being advised to move northward, I came with my wife to Philadelphia, where I have laboured for a livelihood upwards of two years, in summer mostly along shore in vessels and stores, and sawing wood in the winter—My mother was set free by Phineas Nickson, my sister by John Trueblood, and both taken up and sold into slavery, myself deprived of the consolation of seeing them, without being exposed to the like grievous oppression.

I Thomas Pritchet was set free by my master, Thomas Pritchet, who furnished me with land to raise provisions for my use, where I built myself a house, cleared a sufficient spot of woodland to produce ten bushels of corn, and the second year about fifteen, the third, had as much planted as I suppose would have produced thirty bushels; this I was obliged to leave about one month before it was fit for gathering, being threatened by Holland Lockwood, who married my said master’s widow, that if I would not come and serve him, he would apprehend me, and send me to the West-Indies; Enoch Ralph also threatening to send me to gaol, and sell me for the good of the country: being thus in jeopardy, I left my little farm with my small stock and utensils, and my corn standing, and escaped by night into Virginia, where shipping myself for Boston, I was through stress of weather landed in New-York, where I served as a waiter seventeen months; but my mind being distressed on account of the situation of my wife and children, I returned to Norfolk in Virginia, with a hope of at least seeing them, if I could not obtain their freedom; but finding I was advertised in the newspaper, twenty dollars the reward for apprehending me, my dangerous situation obliged me to leave Virginia, disappointed of seeing my wife and children, coming to Philadelphia, where I resided in the employment of a waiter upwards of two years.

In addition to the hardship of our own case, as above set forth, we believe ourselves warranted, on the present occasion, in offering to your consideration the singular case of a fellow black now confined in the gaol of this city, under sanction of the act of general government, called the Fugitive Law, as it appears to us a flagrant proof how far human beings, merely on account of colour and complexion, are through prevailing prejudice out-lawed and excluded from common justice and common humanity, by the operation of such partial laws, in support of habits and customs cruelly oppressive. This man, having been many years past manumitted by his master in North-Carolina, was under the authority of the aforementioned law of that state, sold again into slavery, and, after having served his purchaser upwards of six years, made his escape to Philadelphia, where he has resided eleven years, having a wife and four children; and by an agent of the Carolina claimer, has been lately apprehended and committed to prison, his said claimer, soon after the man’s escaping from him, having advertised him, offering a reward of ten silver dollars to any person that would bring him back, or five time that sum to any person that would make due proof of his being killed, and no questions asked by whom.

We beseech your impartial attention to our hard condition, not only with respect to our personal sufferings as freemen, but as a class of that people who, distinguished by colour, are therefore, with a degrading partiality, considered by many, even of those in eminent station, as unentitled to that public justice and protection which is the great object of government. We indulge not a hope, or presume to ask for the interposition of your honourable body, beyond the extent of your constitutional power or influence, yet are willing to believe your serious, disinterested and candid consideration of the premises, under the benign impressions of equity and mercy, producing upright exertion of what is in your power, may not be without some salutary effect, but for our relief as a people, and toward the removal of obstructions to public order and well being.

If notwithstanding all that has been publicly avowed as essential principles respecting the extent of human right to freedom; notwithstanding we have had that right restored to us, so far as was in the power of those by whom we were held as slaves, we cannot claim the privilege of representation in your councils, yet we trust we may address you as fellow men, who, under God the sovereign ruler of the universe, are intrusted with the distribution of justice, for the terror of evil doers, the encouragement and protection of the innocent, not doubting that you are men of liberal minds, susceptible of benevolent feelings and clear conception of rectitude, to a catholic extent, who can admit that black people (servile as their condition generally is throughout this continent) have natural affections, social and domestic attachments and sensibilities; and that therefore we may hope for a share in your sympathetic attention while we represent that the unconstitutional bondage in which multitudes of our fellows in complexion are held, is to us a subject sorrowfully affecting; for we cannot conceive their condition (more especially those who have been emancipated, and tasted the sweets of liberty, and again reduced to slavery by kidnappers and man-stealers) to be less afflicting or deplorable than the situation of citizens of the United States, captivated and enslaved through the unrighteous policy prevalent in Algiers— We are far from considering all those who retain slaves as wilful oppressors, being well assured that numbers in the state from whence we are exiles, hold their slaves in bondage not of choice, but possessing them by inheritance feel their minds burthened under the slavish restraint of legal impediments to doing that justice which they are convinced is due to fellow rationals.—May we not be allowed to consider this stretch of power, morally and politically, a governmental defect, if not a direct violation of the declared fundamental principles of the constitution; and finally, is not some remedy for an evil of such magnitude highly worthy of the deep enquiry and unfeigned zeal of the supreme legislative body of [a] free and enlightened people? Submitting our cause to God and humbly craving your best aid and influence, as you may be favoured and directed by that wisdom which is from above, wherewith that you may be eminently dignified and rendered more conspicuously, in the view of nations, a blessing to the people you represent, is the sincere prayer of your petitioners.

JACOB NICHOLSON His JUPITER X NICHOLSON Mark His JOB X ALBERT Mark His THOMAS X PRITCHET Mark

Philadelphia, January 23, 1797

Source: Petition drafted by Absalom Jones and submitted to the US Congress by Jacob Nicholson, Jupiter Nicholson, Job Albert, and Thomas Pritchet, January 23, 1797, in Thomas Carpenter, The American Senator. Or a Copious and Impartial Report of the Debates in the Congress of the United States, vol. 2 (Philadelphia, 1797), pp. 286–290.

Petition to Free Enslaved People by Absalom Jones, January 23, 1797

To the President, Senate, and House of Representatives.

Respectfully:

. . . as freemen liberated under the hand and seal of humane and conscientious masters . . . restoring us to our native right of freedom, was confirmed by judgment of the Superior court of North-Carolina . . . yet not long after this decision, a law of that state was enacted, under which men of cruel disposition . . . received . . . authority in violently seizing, imprisoning and selling into slavery, such as had been so emancipated; whereby we were reduced to . . . seeking refuge in such parts of the Union where more regard is paid . . . in favour of liberty and the common right of men, several hundreds under our circumstance having, in consequence of the said law,been hunted day and night, like beasts of the forest, by armed men with dogs, and made prey of as free and lawful plunder . . .

We beseech your impartial attention to our hard condition, not only with respect to our personal sufferings as freemen, but as a class of that people who, distinguished by colour, are therefore . . . considered by many . . . as unentitled to that public justice and protection which is the great object of government. We indulge not a hope, or presume to ask for . . . your honourable body, beyond the extent of your constitutional power . . . for our relief as a people, and toward the removal of obstructions to public order and well being.

. . . we trust we may address you as fellow men . . . who can admit that black people . . . have natural affections . . . and that therefore we may hope for a share in your sympathetic attention while we represent that the unconstitutional bondage in which multitudes of our fellows . . . are held . . . for we cannot conceive their condition (more especially those who have been emancipated, and tasted the sweets of liberty, and again reduced to slavery by kidnappers and man-stealers) to be less afflicting or deplorable than the situation of citizens of the United States . . .

Source: Petition drafted by Absalom Jones and submitted to the US Congress by Jacob Nicholson, Jupiter Nicholson, Job Albert, and Thomas Pritchet, January 23, 1797, in Thomas Carpenter, The American Senator. Or a Copious and Impartial Report of the Debates in the Congress of the United States, vol. 2 (Philadelphia, 1797), pp. 286–290.

humane - compassionate

conscientious - honorable

disposition - character

emancipated - free from bondage/slavery

plunder - to take by force

affections - feelings/emotions

Background

In response to a North Carolina law that legalized the capture and reenslavement of emancipated people, Absalom Jones drafted a petition to the US Congress on behalf of four recently freed men living in Philadelphia. The petitioners implored Congress to end this treacherous practice, which, they argued, was in direct violation of the Constitution.

Transcript

Petition drafted by Absalom Jones and submitted to the United States Congress by

Jacob Nicholson, Jupiter Nicholson, Job Albert, and Thomas Pritchet, January 23, 1797

To the President, Senate, and House of Representatives.

The PETITION and REPRESENTATION of the undernamed FREEMEN,

Respectfully Sheweth:

THAT being of African descent, late inhabitants and natives of North Carolina, to you only, under God, can we apply with any hope of effect, for redress of our grievances, having been compelled to leave the state wherein we had a right of residence, as freemen liberated under the hand and seal of humane and conscientious masters, the validity of which act of justice, in restoring us to our native right of freedom, was confirmed by judgment of the Superior court of North-Carolina, wherein it was brought to trial; yet not long after this decision, a law of that state was enacted, under which men of cruel disposition, and void of just principle, received countenance and authority in violently seizing, imprisoning and selling into slavery, such as had been so emancipated; whereby we were reduced to the necessity of separating from some of our nearest and most tender connections, and of seeking refuge in such parts of the Union where more regard is paid to the public declaration in favour of liberty and the common right of men, several hundreds under our circumstance having, in consequence of the said law, been hunted day and night, like beasts of the forest, by armed men with dogs, and made prey of as free and lawful plunder. Among others thus exposed, I Jupiter Nicholson, or Perquimons county, North-Carolina, after being set free by my master, Thomas Nicholson, and having been about two years employed as a seaman in the service of Zachary Nickson, on coming on shore, was pursued by men with dog and arms; but was favoured to escape by night to Virginia, with my wife, who was manumited by Gabriel Cosand, where I resided about four years in the town of Portsmouth, chiefly employed in sawing boards and scantling; from thence I removed with my wife to Philadelphia, where I have been employed at times by water, working along shore, or sawing wood. I left behind me a father and mother, who were manumitted by Thomas Nicholson and Zachary Dickson; they have been since taken up with a beloved brother, and sold into cruel bondage.

I Jacob Nicholson, also of North Carolina, being set free by my master, Joseph Nicholson, but continuing to live with him till being pursued day and night I was obliged to leave my abode, sleep in the woods, and stacks in the fields, &c. to escape the hands of violent men, who, induced by the profit afforded them by law, followed this course as a business; at length by night I made my escape, leaving a mother, one child and two brothers, to see whom I dare not return.

I Job Albert, manumitted by Benjamin Albertson, who was my careful guardian to protect me from being afterwards taken and sold, providing me with a house to accommodate me and my wife, who was liberated by William Robertson; but we were night and day hunted by men armed with guns, swords and pistols, accompanied with mastiff dogs; from whose violence being one night apprehensive of immediate danger, I left my dwelling locked and barred and fastened with a chain, lying at some distance from it, while my wife was by my kind master locked up under his roof; I heard them break into my house, where not finding their prey, they got but a small booty, a handkerchief of about a dollar value, and some provisions; but not long after I was discovered and seized by Alexander Stafford, William Stafford and Thomas Creesy, who were armed with guns and clubs: after binding me with my hands behind me, and a rope round my arms and body, they took me about four miles to Hartford prison, where I lay four weeks, suffering much for want of provision; from thence, with the assistance of a fellow-prisoner, a white man, I made my escape, and for three dollars was conveyed with my wife by a humane person, in a covered waggon by night, to Virginia, where, in the neighborhood of Portsmouth, I continued unmolested about four years, being chiefly engaged in sawing boards and blank. On being advised to move northward, I came with my wife to Philadelphia, where I have laboured for a livelihood upwards of two years, in summer mostly along shore in vessels and stores, and sawing wood in the winter—My mother was set free by Phineas Nickson, my sister by John Trueblood, and both taken up and sold into slavery, myself deprived of the consolation of seeing them, without being exposed to the like grievous oppression.

I Thomas Pritchet was set free by my master, Thomas Pritchet, who furnished me with land to raise provisions for my use, where I built myself a house, cleared a sufficient spot of woodland to produce ten bushels of corn, and the second year about fifteen, the third, had as much planted as I suppose would have produced thirty bushels; this I was obliged to leave about one month before it was fit for gathering, being threatened by Holland Lockwood, who married my said master’s widow, that if I would not come and serve him, he would apprehend me, and send me to the West-Indies; Enoch Ralph also threatening to send me to gaol, and sell me for the good of the country: being thus in jeopardy, I left my little farm with my small stock and utensils, and my corn standing, and escaped by night into Virginia, where shipping myself for Boston, I was through stress of weather landed in New-York, where I served as a waiter seventeen months; but my mind being distressed on account of the situation of my wife and children, I returned to Norfolk in Virginia, with a hope of at least seeing them, if I could not obtain their freedom; but finding I was advertised in the newspaper, twenty dollars the reward for apprehending me, my dangerous situation obliged me to leave Virginia, disappointed of seeing my wife and children, coming to Philadelphia, where I resided in the employment of a waiter upwards of two years.

In addition to the hardship of our own case, as above set forth, we believe ourselves warranted, on the present occasion, in offering to your consideration the singular case of a fellow black now confined in the gaol of this city, under sanction of the act of general government, called the Fugitive Law, as it appears to us a flagrant proof how far human beings, merely on account of colour and complexion, are through prevailing prejudice out-lawed and excluded from common justice and common humanity, by the operation of such partial laws, in support of habits and customs cruelly oppressive. This man, having been many years past manumitted by his master in North-Carolina, was under the authority of the aforementioned law of that state, sold again into slavery, and, after having served his purchaser upwards of six years, made his escape to Philadelphia, where he has resided eleven years, having a wife and four children; and by an agent of the Carolina claimer, has been lately apprehended and committed to prison, his said claimer, soon after the man’s escaping from him, having advertised him, offering a reward of ten silver dollars to any person that would bring him back, or five time that sum to any person that would make due proof of his being killed, and no questions asked by whom.

We beseech your impartial attention to our hard condition, not only with respect to our personal sufferings as freemen, but as a class of that people who, distinguished by colour, are therefore, with a degrading partiality, considered by many, even of those in eminent station, as unentitled to that public justice and protection which is the great object of government. We indulge not a hope, or presume to ask for the interposition of your honourable body, beyond the extent of your constitutional power or influence, yet are willing to believe your serious, disinterested and candid consideration of the premises, under the benign impressions of equity and mercy, producing upright exertion of what is in your power, may not be without some salutary effect, but for our relief as a people, and toward the removal of obstructions to public order and well being.

If notwithstanding all that has been publicly avowed as essential principles respecting the extent of human right to freedom; notwithstanding we have had that right restored to us, so far as was in the power of those by whom we were held as slaves, we cannot claim the privilege of representation in your councils, yet we trust we may address you as fellow men, who, under God the sovereign ruler of the universe, are intrusted with the distribution of justice, for the terror of evil doers, the encouragement and protection of the innocent, not doubting that you are men of liberal minds, susceptible of benevolent feelings and clear conception of rectitude, to a catholic extent, who can admit that black people (servile as their condition generally is throughout this continent) have natural affections, social and domestic attachments and sensibilities; and that therefore we may hope for a share in your sympathetic attention while we represent that the unconstitutional bondage in which multitudes of our fellows in complexion are held, is to us a subject sorrowfully affecting; for we cannot conceive their condition (more especially those who have been emancipated, and tasted the sweets of liberty, and again reduced to slavery by kidnappers and man-stealers) to be less afflicting or deplorable than the situation of citizens of the United States, captivated and enslaved through the unrighteous policy prevalent in Algiers— We are far from considering all those who retain slaves as wilful oppressors, being well assured that numbers in the state from whence we are exiles, hold their slaves in bondage not of choice, but possessing them by inheritance feel their minds burthened under the slavish restraint of legal impediments to doing that justice which they are convinced is due to fellow rationals.—May we not be allowed to consider this stretch of power, morally and politically, a governmental defect, if not a direct violation of the declared fundamental principles of the constitution; and finally, is not some remedy for an evil of such magnitude highly worthy of the deep enquiry and unfeigned zeal of the supreme legislative body of [a] free and enlightened people? Submitting our cause to God and humbly craving your best aid and influence, as you may be favoured and directed by that wisdom which is from above, wherewith that you may be eminently dignified and rendered more conspicuously, in the view of nations, a blessing to the people you represent, is the sincere prayer of your petitioners.

JACOB NICHOLSON His JUPITER X NICHOLSON Mark His JOB X ALBERT Mark His THOMAS X PRITCHET Mark

Philadelphia, January 23, 1797

Source: Petition drafted by Absalom Jones and submitted to the US Congress by Jacob Nicholson, Jupiter Nicholson, Job Albert, and Thomas Pritchet, January 23, 1797, in Thomas Carpenter, The American Senator. Or a Copious and Impartial Report of the Debates in the Congress of the United States, vol. 2 (Philadelphia, 1797), pp. 286–290.

Excerpt

Petition to Free Enslaved People by Absalom Jones, January 23, 1797

To the President, Senate, and House of Representatives.

Respectfully:

. . . as freemen liberated under the hand and seal of humane and conscientious masters . . . restoring us to our native right of freedom, was confirmed by judgment of the Superior court of North-Carolina . . . yet not long after this decision, a law of that state was enacted, under which men of cruel disposition . . . received . . . authority in violently seizing, imprisoning and selling into slavery, such as had been so emancipated; whereby we were reduced to . . . seeking refuge in such parts of the Union where more regard is paid . . . in favour of liberty and the common right of men, several hundreds under our circumstance having, in consequence of the said law,been hunted day and night, like beasts of the forest, by armed men with dogs, and made prey of as free and lawful plunder . . .

We beseech your impartial attention to our hard condition, not only with respect to our personal sufferings as freemen, but as a class of that people who, distinguished by colour, are therefore . . . considered by many . . . as unentitled to that public justice and protection which is the great object of government. We indulge not a hope, or presume to ask for . . . your honourable body, beyond the extent of your constitutional power . . . for our relief as a people, and toward the removal of obstructions to public order and well being.

. . . we trust we may address you as fellow men . . . who can admit that black people . . . have natural affections . . . and that therefore we may hope for a share in your sympathetic attention while we represent that the unconstitutional bondage in which multitudes of our fellows . . . are held . . . for we cannot conceive their condition (more especially those who have been emancipated, and tasted the sweets of liberty, and again reduced to slavery by kidnappers and man-stealers) to be less afflicting or deplorable than the situation of citizens of the United States . . .

Source: Petition drafted by Absalom Jones and submitted to the US Congress by Jacob Nicholson, Jupiter Nicholson, Job Albert, and Thomas Pritchet, January 23, 1797, in Thomas Carpenter, The American Senator. Or a Copious and Impartial Report of the Debates in the Congress of the United States, vol. 2 (Philadelphia, 1797), pp. 286–290.

humane - compassionate

conscientious - honorable

disposition - character

emancipated - free from bondage/slavery

plunder - to take by force

affections - feelings/emotions