Patrick Henry on the Evils of Slavery, 1773

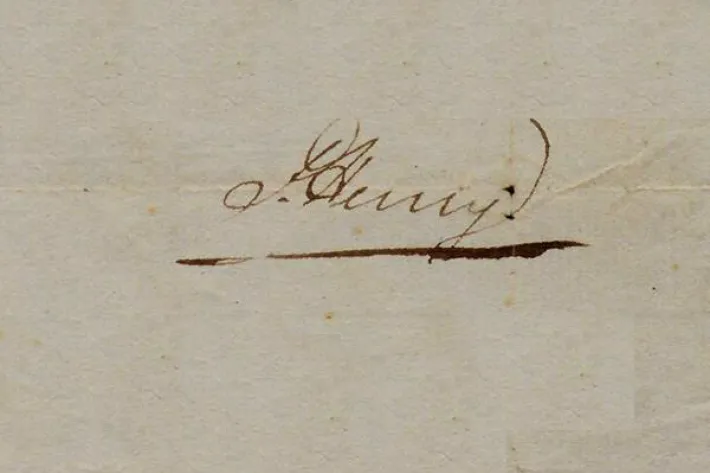

Signature of Patrick Henry, (Gilder Lehrman Institute)

Patrick Henry wrote this letter on the subject of slavery in early 1773. He regarded slavery as an evil practice yet remained a slaveholder himself. Acknowledging his own hypocrisy, he here expresses his admiration for Christians such as the anti-slavery Quaker John Alsop of Hudson, New York, to whom he addressed the letter.

A Letter from Patrick Henry to John Alsop, January 13, 1773

HANOVER, Va., Jan. 13, 1773.

DEAR SIR:—I take this opportunity to acknowledge the receipt of ANTHONY BENEZET’s book against the slave trade. I thank you for it. It is not a little surprising that Christianity, whose chief excellence consists in softening the human heart, in cherishing and improving its finer feelings, should encourage a practice so totally repugnant to the first impressions of right and wrong. What adds to the wonder is, that this abominable practice has been introduced in the most enlightened ages Times that seem to have pretensions to boast of high improvements in arts, sciences and refined morality, have brought into general use, and guarded by many laws, a species of violence and tyranny which our more rude and barbarous, but more honest, ancestors detested. Is it not amazing that at the time when the rights of humanity are defined and understood with precision, in a country, above all others, fond of liberty—that in such an age and in such a country we find men professing a religion the most humane, mild, meek, gentle and generous, adopting a principle as repugnant to humanity as it is inconsistent with the Bible and destructive to liberty? Every thinking, honest man rejects it in speculation. How few, in practice, from conscientious motives! The world, in general, has denied your people a share of its honors; but the wise will ascribe to you a just tribute of virtuous praise for the practice of a train of virtues, among which your disagreement to Slavery will be principally ranked. I cannot but wish well to a people whose system imitates the example of Him whose life was perfect; and believe me, I shall honor the Quakers for their noble efforts to abolish Slavery. It was equally calculated to promote moral and political good. Would any one believe that I am master of slaves by my own purchase? I am drawn along by the general inconvenience of living without them. I will not—I cannot justify it, however culpable my conduct. I will so far pay my devoir to Virtue, as to own the excellence and rectitude of her precepts, and to lament my conformity to them. I believe a time will come when an opportunity will be afforded to abolish this lamentable evil. Everything we can do, is to improve it, if it happens in our day; if not, let us transmit to our descendants, together with our slaves, a pity for their unhappy lot, and an abhorrence of Slavery. If we cannot reduce this wished-for reformation to practice, let us treat the unhappy victims with lenity. It is the furthest advancement we can make toward justice. It is a debt we owe to the purity of our religion, to show that it is at variance with that law which warrants Slavery. Here is an instance that silent meetings (the scoff of Rev. doctors) have done that which learned and elaborate preaching cannot effect; so much preferable are the dictates of conscience, and a steady attention to its feelings, above the teaching of those men who pretend to have found a better guide. I exhort you to persevere in so worthy a resolution. Some of your people disagree, or at least are lukewarm in the Abolition of Slavery. Many treat the resolution of your meeting with ridicule; and among those who throw ridicule and contempt on it are clergymen whose surest guard against both ridicule and contempt, is a certain act of Assembly. I know not where to stop. I could say many things on this subject, a serious review of which gives a gloomy perspective in future times. Excuse this scrawl, and believe me, with esteem, your humble servant. PARTRICK HENRY, Jr.

Source: Patrick Henry to John Alsop, January 13, 1773, in Friends’ Intelligencer 17 (July 21, 1860), ed. by an Association of Friends (Philadelphia: William W. Moore, 1861), p. 303.

A Letter from Patrick Henry to John Alsop, January 13, 1773

HANOVER, Va., Jan. 13, 1773.

DEAR SIR: — I take this opportunity to acknowledge the receipt of ANTHONY BENEZET’s book against the slave trade . . . It is not a little surprising that Christianity, whose chief excellence consists in softening the human heart . . . should encourage a practice so totally repugnant to the first impressions of right and wrong. What adds to the wonder is, that this abominable practice has been introduced in the most enlightened ages . . .

The world, in general, has denied your people a share of its honors; but the wise will ascribe to you a just tribute . . . among which your disagreement to Slavery will be principally ranked . . . I shall honor the Quakers for their noble efforts to abolish Slavery. It was equally calculated to promote moral and political good.

Would any one believe that I am master of slaves by my own purchase? I am drawn along by the general inconvenience of living without them . . . I believe a time will come when an opportunity will be afforded to abolish this lamentable evil. Everything we can do, is to improve it, if it happens in our day; if not, let us transmit to our descendants, together with our slaves, a pity for their unhappy lot, and an abhorrence of Slavery . . . It is a debt we owe to the purity of our religion, to show that it is at variance with that law which warrants Slavery . . .

I know not where to stop. I could say many things on this subject, a serious review of which gives a gloomy perspective in future times. Excuse this scrawl, and believe me, with esteem, your humble servant.

PATRICK HENRY, Jr.

Source: Patrick Henry to John Alsop, January 13, 1773, in Friends’ Intelligencer 17 (July 21, 1860), ed. by an Association of Friends (Philadelphia: William W. Moore, 1861), p. 303.

repugnant - unacceptable

abhorrence - hatred

Background

Patrick Henry wrote this letter on the subject of slavery in early 1773. He regarded slavery as an evil practice yet remained a slaveholder himself. Acknowledging his own hypocrisy, he here expresses his admiration for Christians such as the anti-slavery Quaker John Alsop of Hudson, New York, to whom he addressed the letter.

Transcript

A Letter from Patrick Henry to John Alsop, January 13, 1773

HANOVER, Va., Jan. 13, 1773.

DEAR SIR:—I take this opportunity to acknowledge the receipt of ANTHONY BENEZET’s book against the slave trade. I thank you for it. It is not a little surprising that Christianity, whose chief excellence consists in softening the human heart, in cherishing and improving its finer feelings, should encourage a practice so totally repugnant to the first impressions of right and wrong. What adds to the wonder is, that this abominable practice has been introduced in the most enlightened ages Times that seem to have pretensions to boast of high improvements in arts, sciences and refined morality, have brought into general use, and guarded by many laws, a species of violence and tyranny which our more rude and barbarous, but more honest, ancestors detested. Is it not amazing that at the time when the rights of humanity are defined and understood with precision, in a country, above all others, fond of liberty—that in such an age and in such a country we find men professing a religion the most humane, mild, meek, gentle and generous, adopting a principle as repugnant to humanity as it is inconsistent with the Bible and destructive to liberty? Every thinking, honest man rejects it in speculation. How few, in practice, from conscientious motives! The world, in general, has denied your people a share of its honors; but the wise will ascribe to you a just tribute of virtuous praise for the practice of a train of virtues, among which your disagreement to Slavery will be principally ranked. I cannot but wish well to a people whose system imitates the example of Him whose life was perfect; and believe me, I shall honor the Quakers for their noble efforts to abolish Slavery. It was equally calculated to promote moral and political good. Would any one believe that I am master of slaves by my own purchase? I am drawn along by the general inconvenience of living without them. I will not—I cannot justify it, however culpable my conduct. I will so far pay my devoir to Virtue, as to own the excellence and rectitude of her precepts, and to lament my conformity to them. I believe a time will come when an opportunity will be afforded to abolish this lamentable evil. Everything we can do, is to improve it, if it happens in our day; if not, let us transmit to our descendants, together with our slaves, a pity for their unhappy lot, and an abhorrence of Slavery. If we cannot reduce this wished-for reformation to practice, let us treat the unhappy victims with lenity. It is the furthest advancement we can make toward justice. It is a debt we owe to the purity of our religion, to show that it is at variance with that law which warrants Slavery. Here is an instance that silent meetings (the scoff of Rev. doctors) have done that which learned and elaborate preaching cannot effect; so much preferable are the dictates of conscience, and a steady attention to its feelings, above the teaching of those men who pretend to have found a better guide. I exhort you to persevere in so worthy a resolution. Some of your people disagree, or at least are lukewarm in the Abolition of Slavery. Many treat the resolution of your meeting with ridicule; and among those who throw ridicule and contempt on it are clergymen whose surest guard against both ridicule and contempt, is a certain act of Assembly. I know not where to stop. I could say many things on this subject, a serious review of which gives a gloomy perspective in future times. Excuse this scrawl, and believe me, with esteem, your humble servant. PARTRICK HENRY, Jr.

Source: Patrick Henry to John Alsop, January 13, 1773, in Friends’ Intelligencer 17 (July 21, 1860), ed. by an Association of Friends (Philadelphia: William W. Moore, 1861), p. 303.

Excerpt

A Letter from Patrick Henry to John Alsop, January 13, 1773

HANOVER, Va., Jan. 13, 1773.

DEAR SIR: — I take this opportunity to acknowledge the receipt of ANTHONY BENEZET’s book against the slave trade . . . It is not a little surprising that Christianity, whose chief excellence consists in softening the human heart . . . should encourage a practice so totally repugnant to the first impressions of right and wrong. What adds to the wonder is, that this abominable practice has been introduced in the most enlightened ages . . .

The world, in general, has denied your people a share of its honors; but the wise will ascribe to you a just tribute . . . among which your disagreement to Slavery will be principally ranked . . . I shall honor the Quakers for their noble efforts to abolish Slavery. It was equally calculated to promote moral and political good.

Would any one believe that I am master of slaves by my own purchase? I am drawn along by the general inconvenience of living without them . . . I believe a time will come when an opportunity will be afforded to abolish this lamentable evil. Everything we can do, is to improve it, if it happens in our day; if not, let us transmit to our descendants, together with our slaves, a pity for their unhappy lot, and an abhorrence of Slavery . . . It is a debt we owe to the purity of our religion, to show that it is at variance with that law which warrants Slavery . . .

I know not where to stop. I could say many things on this subject, a serious review of which gives a gloomy perspective in future times. Excuse this scrawl, and believe me, with esteem, your humble servant.

PATRICK HENRY, Jr.

Source: Patrick Henry to John Alsop, January 13, 1773, in Friends’ Intelligencer 17 (July 21, 1860), ed. by an Association of Friends (Philadelphia: William W. Moore, 1861), p. 303.

repugnant - unacceptable

abhorrence - hatred