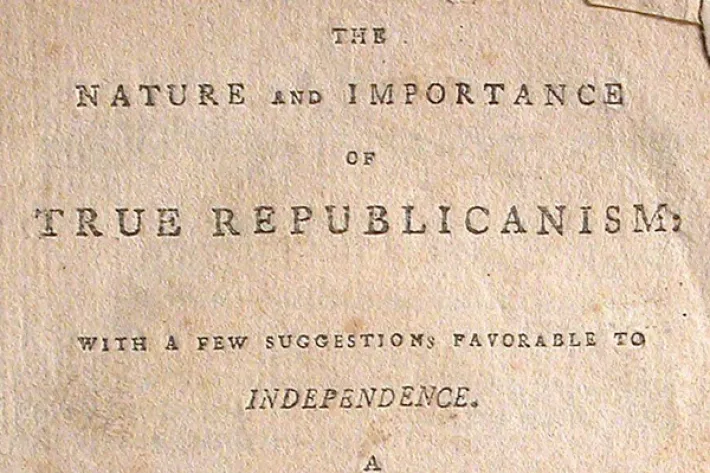

“The Nature and Importance of True Republicanism,” 1801

The Nature and Importance of True Republicanism, with a Few Suggestions Favorable to Independence: A Discourse Delivered at Rutland (Vermont) the Fourth of July 1801, it being the 25th Anniversary of American Independence

In his 1801 speech on true republicanism, Haynes comes across as a kind of prophet. He not only foresees struggles to come such as the abolition movement of the 1850s and the Civil War, but sometimes employs language that, from our historical perspective, sounds uncannily familiar, as if written by Frederick Douglass or Abraham Lincoln.

Excerpts from Lemuel Haynes’s “The Nature and Importance of True Republicanism,” 1801

. . . Our beneficent creator has furnished us with moral and natural endowments, and they according to common sense, are our own: if so we have a right to use them in every way wherein we make no encroachments on the equal rights of our neighbor.—Others can have no demand on us for what they never gave or for which we are in no sense indebted to them. Every attack of this nature ought to be opposed with the same laudable zeal and abhorrence as if it had been made on our lives. As we stand related to God, it is true we are not our own, yet he allows us this prerogative to exert all our faculties, in behalf of the general good.—The laws of the commonwealth are to defend mankind in the peaceable possession of these invaluable blessings, which equally belong unto all men as their birthright.—As civil regulations respect the community, and all are equally interested in them, we at once argue their origin, viz from the people at large. This is that genuine republicanism that we ought most earnestly to contend for, and is the very foundation of true independence; the excellency, and importance of which, will in the next place be considered.

The benign influence of such a constitution and government, comprised in the above remarks, may be clearly deduced from the considerations, that it is falling in with the divine plan, and coincident with the laws of nature. These rights were given to men by the author of our being, as the best antidote against faction; to meliorate the troubles of life, and to cement mankind in the strictest bonds of friendship and society—Those who oppose such a form of government would invert the order of nature, and the constitution of heaven, and destroy the beauty and harmony of the natural and moral worlds.

. . . When men are made to believe that true dignity consists in outward parade and pompous titles, they forget the thing itself, and the greater part of the community view the other as unattainable, they look up to others as above them, and forget to think for themselves, nor retain their own importance in the scale of being. Hence, under a monarchal government, people are commonly ignorant; they know but little more than to bow to despots, and crouch to them for a piece of bread.

The propriety of this idea will appear strikingly evident by pointing you to the poor Africans, among us. What has reduced them to their present pitiful, abject state? Is it any distinction that the God of nature hath made in their formation? Nay—but being subjected to slavery, by the cruel hands of oppressors, they have been taught to view themselves as a rank of beings far below others, which has suppressed, in a degree, every principle of manhood, and so they become despised, ignorant, and licentious. This shews the effects of despotism, and should fill us with the utmost detestation against every attack on the rights of men: while we cherish and diffuse, with a laudable ambition, that heaven-born liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free. Should we compare those countries, where tyrants are gorged with human blood, to the far more peaceful regions of North America, the contrast would appear striking.

On the whole, does it not appear that a land of liberty is favourable to peace, happiness, virtue and religion, and should be held sacred by mankind? . . .

. . . As a further mean to maintain our rights and immunities, we should beware of discord among ourselves. That a kingdom divided against itself cannot stand, is a divine maxim, and confirmed by long experience. Union in every society is essential to its existence.—Every thing of a petulent and party spirit ought carefully to be avoided.—Candid discussion is useful in every community; while bitterness, invective and enthusiasm, only prejudice the heart and blind the understanding. How often have public occasions, that otherwise might have proved profitable, been rendered more than useless for want of that prudence, moderation and friendship that should always distinguish a free people.—That the unhappy divisions among us, have been greatly stimulated by such means, we have painful evidence. That the press can plead exemption from such an imputation, cannot be admitted.

Foreign powers envy our tranquility, they abhor republicanism; as by it their craft is in danger. They wish in every possible way to separate us, that we may fall an easy prey to their pride and avarice. Next to maintaining our independence, let us cultivate a laudable union among ourselves and this will render us invincible to every rival.

Source: Lemuel Haynes, The Nature and Importance of True Republicanism: With a Few Suggestions Favorable to Independence. A Discourse, Delivered at Rutland, (Vermont,) the Fourth of July, 1801.—It Being the 25th Anniversary of American Independence (Rutland, Vermont, 1801), pp. 7–9, 11–12, and 15–16.

Lemuel Haynes’s “The Nature and Importance of True Republicanism,” 1801

Our beneficent creator has furnished us with moral and natural endowments, and they according to common sense, are our own: if so we have a right to use them in every way wherein we make no encroachments on the equal rights of our neighbor. — This is that genuine republicanism that we ought most earnestly to contend for, and is the very foundation of true independence; the excellency, and importance of which, will in the next place be considered.

The propriety of this idea will appear strikingly evident by pointing you to the poor Africans, among us. What has reduced them to their present pitiful, abject state? Is it any distinction that the God of nature hath made in their formation? Nay — but being subjected to slavery, by the cruel hands of oppressors, they have been taught to view themselves as a rank of beings far below others, which has suppressed, in a degree, every principle of manhood, and so they become despised, ignorant, and licentious . . .

As a further mean to maintain our rights and immunities, we should beware of discord among ourselves. That a kingdom divided against itself cannot stand, is a divine maxim, and confirmed by long experience. Union in every society is essential to its existence.

Foreign powers envy our tranquility, they abhor republicanism; as by it their craft is in danger. They wish in every possible way to separate us, that we may fall an easy prey to their pride and avarice. Next to maintaining our independence, let us cultivate a laudable union among ourselves and this will render us invincible to every rival.

Source: Lemuel Haynes, The Nature and Importance of True Republicanism: With a Few Suggestions Favorable to Independence. A Discourse, Delivered at Rutland, (Vermont,) the Fourth of July, 1801.—It Being the 25th Anniversary of American Independence (Rutland, Vermont, 1801), pp. 7–9, 11–12, and 15–16.

abject - without dignity

maxim - a short story of truth

Background

In his 1801 speech on true republicanism, Haynes comes across as a kind of prophet. He not only foresees struggles to come such as the abolition movement of the 1850s and the Civil War, but sometimes employs language that, from our historical perspective, sounds uncannily familiar, as if written by Frederick Douglass or Abraham Lincoln.

Transcript

Excerpts from Lemuel Haynes’s “The Nature and Importance of True Republicanism,” 1801

. . . Our beneficent creator has furnished us with moral and natural endowments, and they according to common sense, are our own: if so we have a right to use them in every way wherein we make no encroachments on the equal rights of our neighbor.—Others can have no demand on us for what they never gave or for which we are in no sense indebted to them. Every attack of this nature ought to be opposed with the same laudable zeal and abhorrence as if it had been made on our lives. As we stand related to God, it is true we are not our own, yet he allows us this prerogative to exert all our faculties, in behalf of the general good.—The laws of the commonwealth are to defend mankind in the peaceable possession of these invaluable blessings, which equally belong unto all men as their birthright.—As civil regulations respect the community, and all are equally interested in them, we at once argue their origin, viz from the people at large. This is that genuine republicanism that we ought most earnestly to contend for, and is the very foundation of true independence; the excellency, and importance of which, will in the next place be considered.

The benign influence of such a constitution and government, comprised in the above remarks, may be clearly deduced from the considerations, that it is falling in with the divine plan, and coincident with the laws of nature. These rights were given to men by the author of our being, as the best antidote against faction; to meliorate the troubles of life, and to cement mankind in the strictest bonds of friendship and society—Those who oppose such a form of government would invert the order of nature, and the constitution of heaven, and destroy the beauty and harmony of the natural and moral worlds.

. . . When men are made to believe that true dignity consists in outward parade and pompous titles, they forget the thing itself, and the greater part of the community view the other as unattainable, they look up to others as above them, and forget to think for themselves, nor retain their own importance in the scale of being. Hence, under a monarchal government, people are commonly ignorant; they know but little more than to bow to despots, and crouch to them for a piece of bread.

The propriety of this idea will appear strikingly evident by pointing you to the poor Africans, among us. What has reduced them to their present pitiful, abject state? Is it any distinction that the God of nature hath made in their formation? Nay—but being subjected to slavery, by the cruel hands of oppressors, they have been taught to view themselves as a rank of beings far below others, which has suppressed, in a degree, every principle of manhood, and so they become despised, ignorant, and licentious. This shews the effects of despotism, and should fill us with the utmost detestation against every attack on the rights of men: while we cherish and diffuse, with a laudable ambition, that heaven-born liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free. Should we compare those countries, where tyrants are gorged with human blood, to the far more peaceful regions of North America, the contrast would appear striking.

On the whole, does it not appear that a land of liberty is favourable to peace, happiness, virtue and religion, and should be held sacred by mankind? . . .

. . . As a further mean to maintain our rights and immunities, we should beware of discord among ourselves. That a kingdom divided against itself cannot stand, is a divine maxim, and confirmed by long experience. Union in every society is essential to its existence.—Every thing of a petulent and party spirit ought carefully to be avoided.—Candid discussion is useful in every community; while bitterness, invective and enthusiasm, only prejudice the heart and blind the understanding. How often have public occasions, that otherwise might have proved profitable, been rendered more than useless for want of that prudence, moderation and friendship that should always distinguish a free people.—That the unhappy divisions among us, have been greatly stimulated by such means, we have painful evidence. That the press can plead exemption from such an imputation, cannot be admitted.

Foreign powers envy our tranquility, they abhor republicanism; as by it their craft is in danger. They wish in every possible way to separate us, that we may fall an easy prey to their pride and avarice. Next to maintaining our independence, let us cultivate a laudable union among ourselves and this will render us invincible to every rival.

Source: Lemuel Haynes, The Nature and Importance of True Republicanism: With a Few Suggestions Favorable to Independence. A Discourse, Delivered at Rutland, (Vermont,) the Fourth of July, 1801.—It Being the 25th Anniversary of American Independence (Rutland, Vermont, 1801), pp. 7–9, 11–12, and 15–16.

Excerpt

Lemuel Haynes’s “The Nature and Importance of True Republicanism,” 1801

Our beneficent creator has furnished us with moral and natural endowments, and they according to common sense, are our own: if so we have a right to use them in every way wherein we make no encroachments on the equal rights of our neighbor. — This is that genuine republicanism that we ought most earnestly to contend for, and is the very foundation of true independence; the excellency, and importance of which, will in the next place be considered.

The propriety of this idea will appear strikingly evident by pointing you to the poor Africans, among us. What has reduced them to their present pitiful, abject state? Is it any distinction that the God of nature hath made in their formation? Nay — but being subjected to slavery, by the cruel hands of oppressors, they have been taught to view themselves as a rank of beings far below others, which has suppressed, in a degree, every principle of manhood, and so they become despised, ignorant, and licentious . . .

As a further mean to maintain our rights and immunities, we should beware of discord among ourselves. That a kingdom divided against itself cannot stand, is a divine maxim, and confirmed by long experience. Union in every society is essential to its existence.

Foreign powers envy our tranquility, they abhor republicanism; as by it their craft is in danger. They wish in every possible way to separate us, that we may fall an easy prey to their pride and avarice. Next to maintaining our independence, let us cultivate a laudable union among ourselves and this will render us invincible to every rival.

Source: Lemuel Haynes, The Nature and Importance of True Republicanism: With a Few Suggestions Favorable to Independence. A Discourse, Delivered at Rutland, (Vermont,) the Fourth of July, 1801.—It Being the 25th Anniversary of American Independence (Rutland, Vermont, 1801), pp. 7–9, 11–12, and 15–16.

abject - without dignity

maxim - a short story of truth