Lucy Knox’s Love Letter to Henry Knox, 1777

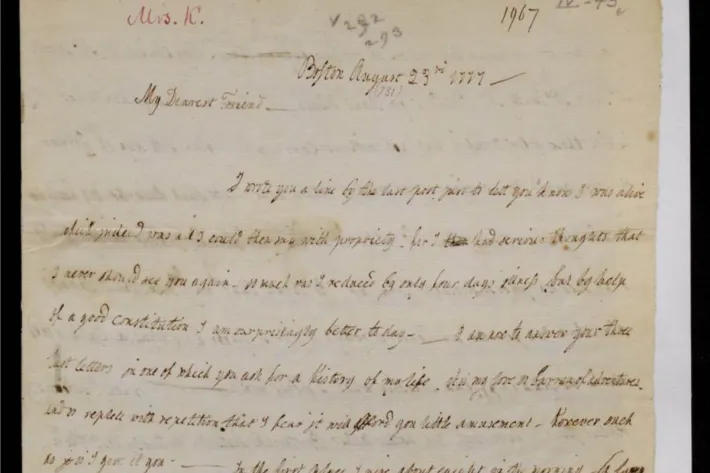

Lucy Flucker Knox, Letter to Henry Knox, August 23, 1777 (The Gilder Lehrman Institute)

Lucy Knox spent much of her early married life alone, as her husband Henry rose through the ranks of the Continental Army. In this letter, the twenty-one-year-old Lucy expressed her unwavering love for Henry, but described her loneliness and desire to know what the future would hold. Although her despair is apparent one can also see her firm resolve in statements such as “I hope you will not consider yourself as commander in chief of your own house, but be convinced that there is such a thing as equal command.”

A Letter from Lucy Knox to Henry Knox, August 23, 1777

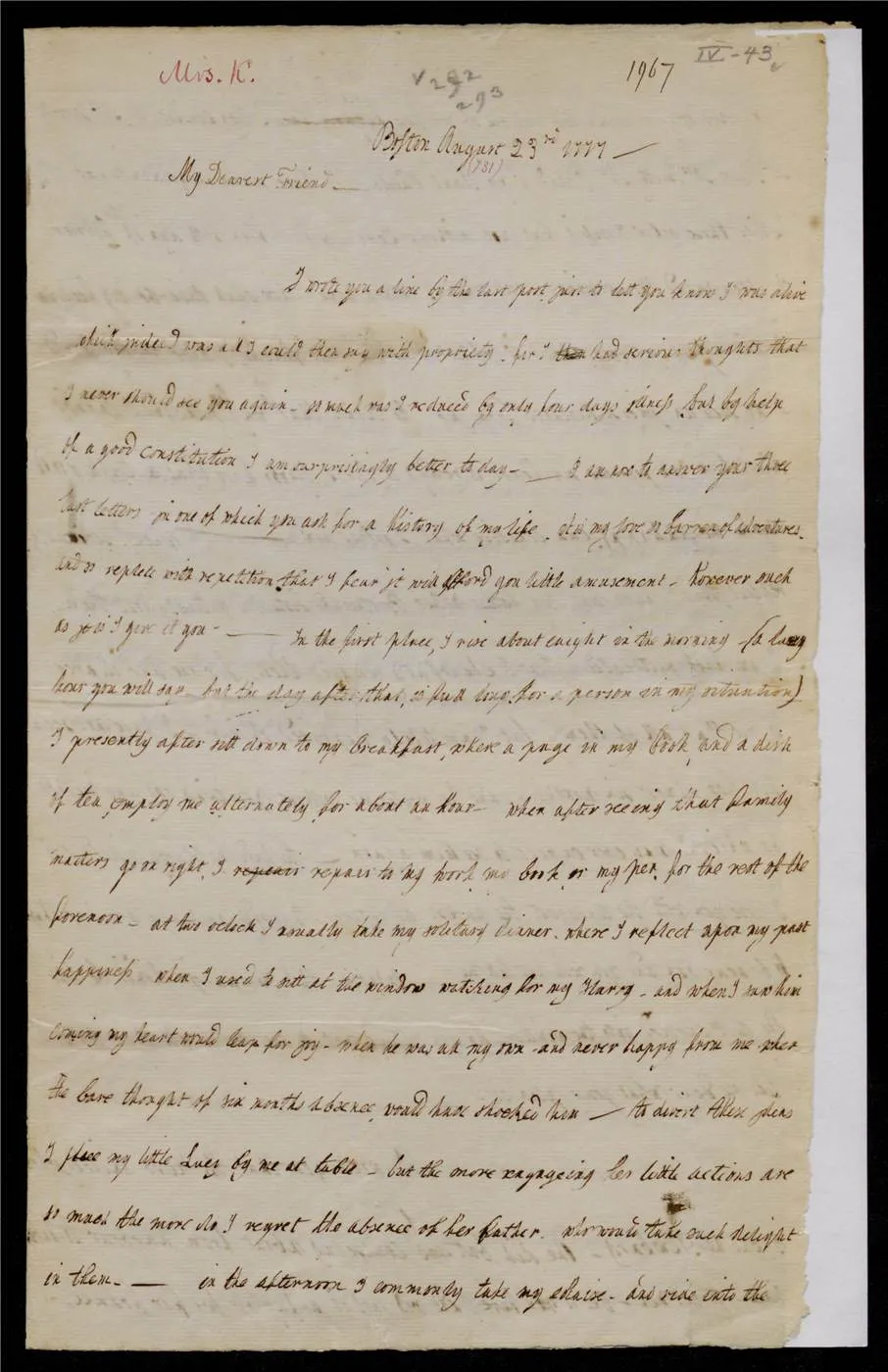

Boston August 23rd 1777 –

My Dearest Friend –

I wrote you a line by the last post just to lett you know I was alive which indeed was all I could then say with propriety for I had serious thoughts that I never should see you again – so much was I reduced by only four days illness but by help of a good constitution I am surprisingly better today — I am now to answer your three last letters in one of which you ask for a history of my life. it is my love so barren of adventures and so replete with repetition that I fear it will afford you little amusement – however such as it is I give it you —In the first place, I rise about eight in the morning (a lazy hour you will say – but the day after that, is full long for a person in my situation) I presently after sitt down to my breakfast, where a page in my book, and a dish of tea, employ me alternately for about an hour – when after seeing that family matters go on right, I repair to my work, my book, or my pen, for the rest of the forenoon – at two oclock I usually take my solitary dinner, where I reflect upon my past happiness when I used to sitt at the window watching for my Harry – and when I saw him coming my heart would leap for joy – when he was all my own and never happy from me when the bare thought of six months absence, would have shocked him – to divert these ideas I place my little Lucy by me at table – but the more engageing her little actions are so much the more do I regret the absence of her father, who would take such delight in them. —in the afternoon I commonly take my chaise, and ride into the country or go to drink tea with one of my few friends. They consist of Mrs Jarviss Mrs Sears Mrs Smith Mrs Pollard and my Aunt Waldo – I have many acquaintance beside these whom I visit but not without Ceremony – when with any of the former I often spend the evening – but when I return home – how shall describe my feelings to find myself intirely alone – to reflect that the only friend I have in the world is at such an imense distance from me – to think that he may be sick and I cannot assist him ah poor me my heart is ready to burst, you who know what a trifle would make me unhappy, can conceive what I suffer now. –

when I seriously reflect that I have lost my father Mother Brother and Sisters – intirely lost them – I am half distracted true I chearfully resigned them for one far dearer to me than all of them – but I am totaly deprived of him – I have not seen him for almost six months – and he writes me without pointing out any method by which I may ever expect to see him again – tis hard my Harry indeed it is I love you with the tenderest the purest affection – I would undergo any hardships to be near you and you will not lett me – suppose this campaign should be like the last carried into the winter – do you intend not to see me in all that time – tell me dear what your plan is –

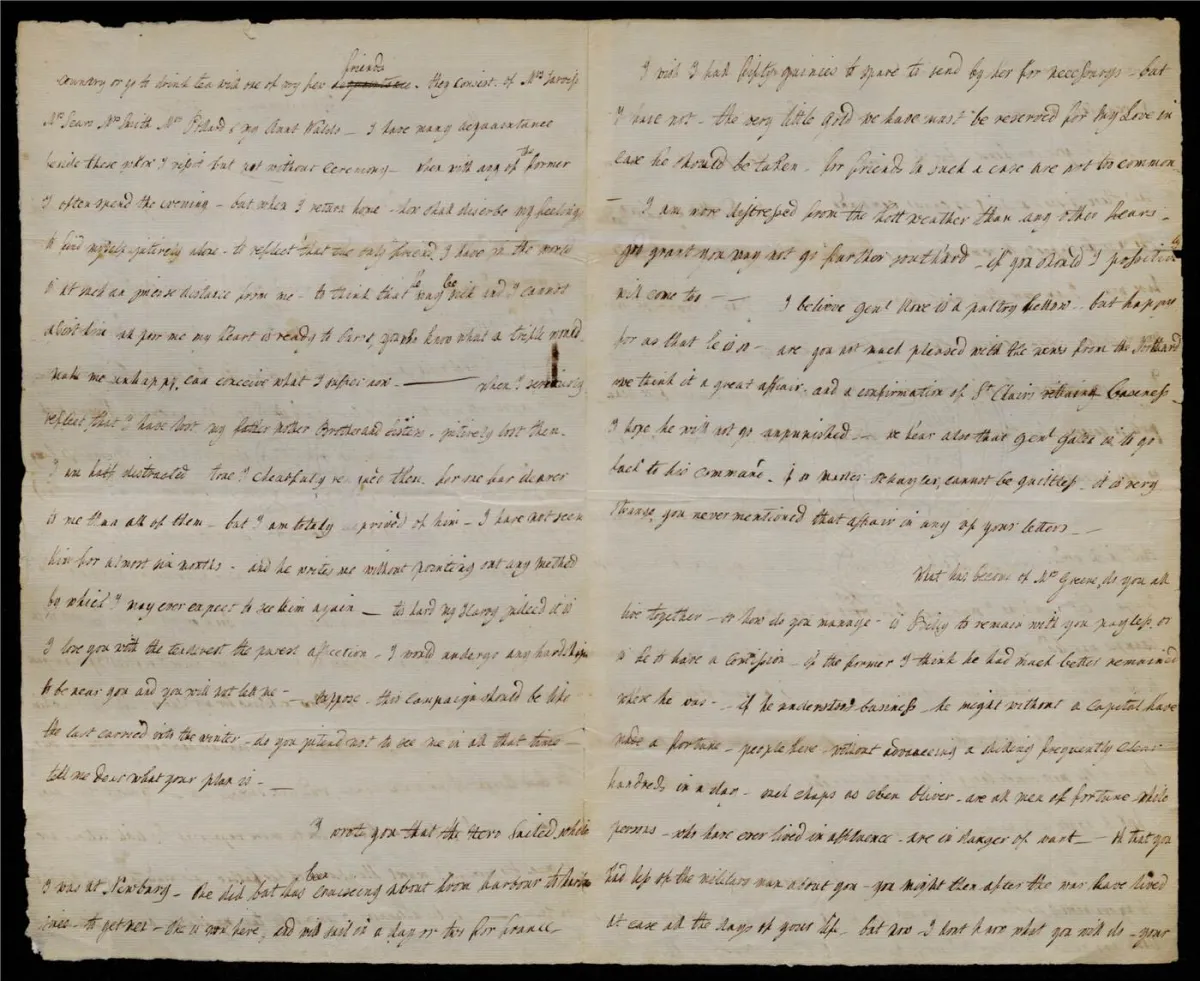

I wrote you that the Hero Sailed while I was at Newburg – She did but has been cruiseing about from harbour to harbour since – to get met – she is now here, and will sail in a day or two for france –

I wish I had fifty guinies to spare to send by her for necessarys – but I have not – the very little gold we have must be reserved for my Love in case he should be taken – for friends in such a case are not too common. – I am more distressed from the hott weather than any other fears – God grant you may not go farther south’ard – if you should I possitively will come too – I believe Genl Howe is a paltry fellow – but happy for as that he is so – are you not much pleased with the news from the Northard we think it is a great affair and a confirmation of St Clairs villainy baseness – I hope he will not go unpunished – we hear also that Genl Gates is to go back to his command. – if so Master Schuyler, cannot be guiltless – it is very strange, you never mentioned that affair in any of your letters –

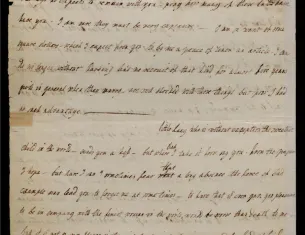

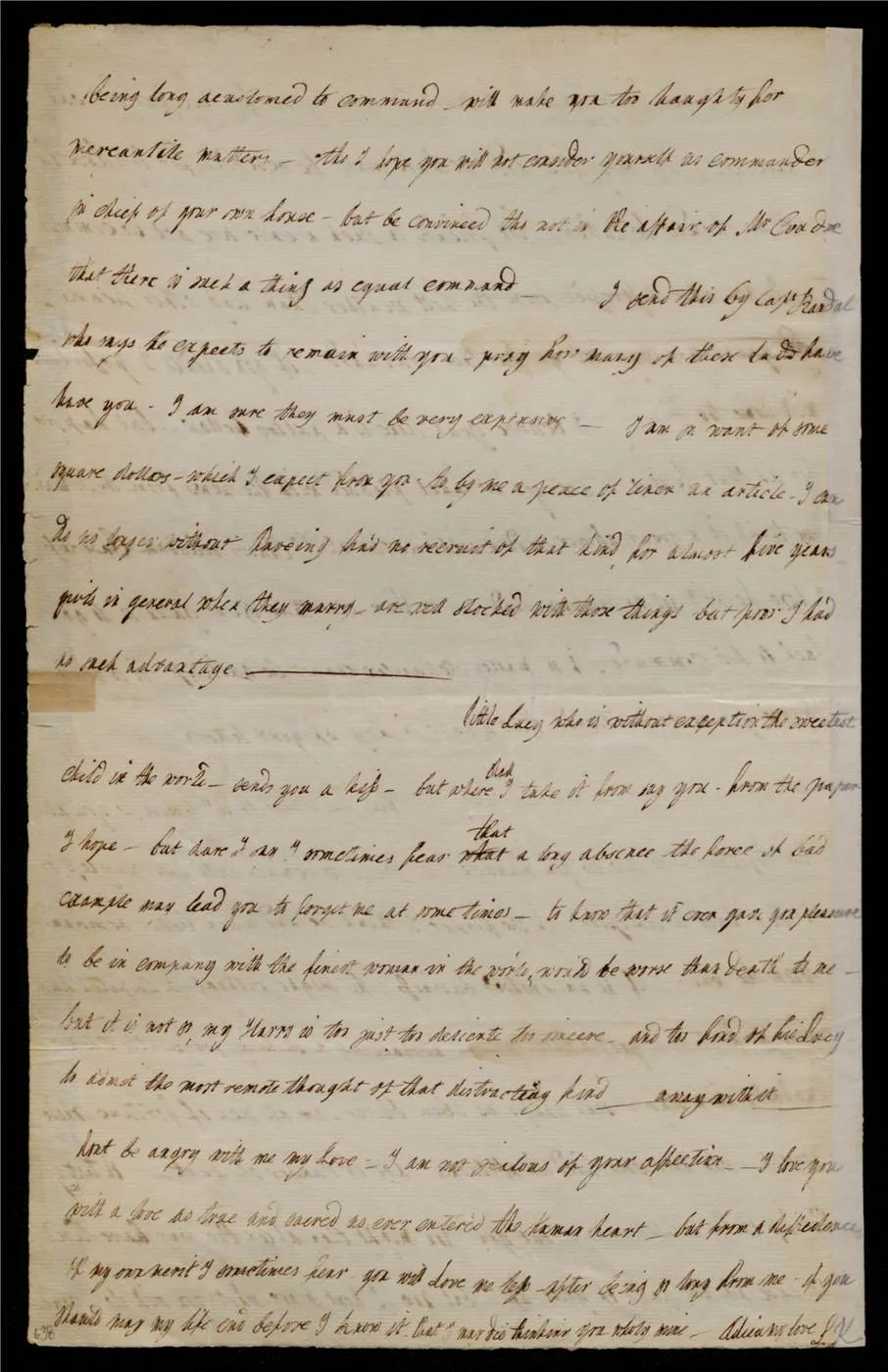

What has become of Mrs Greene, do you all live together – or how do you manage – is Billy to remain with you payless or is he to have a commission – if the former I think he had much better remained where he was – if he understood business he might without a capital have made a fortune – people here – without advanceing a shilling frequently clear hundreds in a day – such chaps as Eben Oliver – are all men of fortune – while persons – who have ever lived in affluence – are in danger of want – oh that you had less of the military man about you – you might then after the war have lived at ease all the days of your life – but now I don't know what you will do – your being long acustomed to command – will make you too haughty for mercantile matters – tho I hope you will not consider yourself as commander in chief of your own house – but be convinced tho not in the affair of Mr Coudre that there is such a thing as equal command – I send this by Capt Randal who says he expects to remain with you – pray how many of these lads have have you – I am sure they must be very expensive – I am in want of some square dollars – which I expect from you to by me a peace of linen an article I can do no longer without haveing had no recruit of that kind for almost five years – girls in general when they marry are well stocked with those things but poor I had no such advantage –

little Lucy who is without exception the sweetest child in the world – sends you a kiss but where shall I take it from say you – from the paper I hope – but dare I say I sometimes fear that a long absence the force of bad example may lead you to forget me at sometimes – to know that it ever gave you pleasure to be in company with the finest woman in the world, would be worse than death to me – but it is not so, my Harry is too just too delicate too sincere – and too fond of his Lucy to admit the most remote thought of that distracting kind – away with it – don’t be angry with me my Love – I am not jealous of your affection – I love you with a love as true and sacred as ever entered the human heart – but from a diffidence of my own merit I sometimes fear you will Love me less – after being so long from me – if you should may my life end before I know it – that I may die thinking you wholly mine –

Adieu my love

LK

Source: Lucy Flucker Knox to Henry Knox, August 23, 1777, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC02437.00638.

Excerpt from a Letter from Lucy Knox to Henry Knox, August 23, 1777

My Dearest Friend —

. . . When I seriously reflect that I have lost my father, mother, brother, and sisters—entirely lost them—I am half distracted, true. I cheerfully resigned them for one far dearer to me than all of them, but I am totally deprived of him—I have not seen him for almost six months—and he writes me without pointing out any method by which I may ever expect to see him again. ’Tis hard, my Harry, indeed it is. I love you with the tenderest, the purest affection. I would undergo any hardships to be near you, and you will not let me. Suppose this campaign should be like the last, carried into the winter. Do you intend not to see me in all that time? Tell me, dear, what your plan is.

Oh, that you had less of the military man about you! You might then, after the war, have lived at ease all the days of your life. But now I don't know what you will do. Your being long accustomed to command will make you too haughty for mercantile matters, though I hope you will not consider yourself as commander in chief of your own house, but be convinced that there is such a thing as equal command.

I love you with a love as true and sacred as ever entered the human heart. But from a diffidence of my own merit I sometimes fear you will love me less after being so long from me. If you should, may my life end before I know it, that I may die thinking you wholly mine. . . .

Source: Lucy Flucker Knox to Henry Knox, August 23, 1777, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC02437.00638.

Background

Lucy Knox spent much of her early married life alone, as her husband Henry rose through the ranks of the Continental Army. In this letter, the twenty-one-year-old Lucy expressed her unwavering love for Henry, but described her loneliness and desire to know what the future would hold. Although her despair is apparent one can also see her firm resolve in statements such as “I hope you will not consider yourself as commander in chief of your own house, but be convinced that there is such a thing as equal command.”

Transcript

A Letter from Lucy Knox to Henry Knox, August 23, 1777

Boston August 23rd 1777 –

My Dearest Friend –

I wrote you a line by the last post just to lett you know I was alive which indeed was all I could then say with propriety for I had serious thoughts that I never should see you again – so much was I reduced by only four days illness but by help of a good constitution I am surprisingly better today — I am now to answer your three last letters in one of which you ask for a history of my life. it is my love so barren of adventures and so replete with repetition that I fear it will afford you little amusement – however such as it is I give it you —In the first place, I rise about eight in the morning (a lazy hour you will say – but the day after that, is full long for a person in my situation) I presently after sitt down to my breakfast, where a page in my book, and a dish of tea, employ me alternately for about an hour – when after seeing that family matters go on right, I repair to my work, my book, or my pen, for the rest of the forenoon – at two oclock I usually take my solitary dinner, where I reflect upon my past happiness when I used to sitt at the window watching for my Harry – and when I saw him coming my heart would leap for joy – when he was all my own and never happy from me when the bare thought of six months absence, would have shocked him – to divert these ideas I place my little Lucy by me at table – but the more engageing her little actions are so much the more do I regret the absence of her father, who would take such delight in them. —in the afternoon I commonly take my chaise, and ride into the country or go to drink tea with one of my few friends. They consist of Mrs Jarviss Mrs Sears Mrs Smith Mrs Pollard and my Aunt Waldo – I have many acquaintance beside these whom I visit but not without Ceremony – when with any of the former I often spend the evening – but when I return home – how shall describe my feelings to find myself intirely alone – to reflect that the only friend I have in the world is at such an imense distance from me – to think that he may be sick and I cannot assist him ah poor me my heart is ready to burst, you who know what a trifle would make me unhappy, can conceive what I suffer now. –

when I seriously reflect that I have lost my father Mother Brother and Sisters – intirely lost them – I am half distracted true I chearfully resigned them for one far dearer to me than all of them – but I am totaly deprived of him – I have not seen him for almost six months – and he writes me without pointing out any method by which I may ever expect to see him again – tis hard my Harry indeed it is I love you with the tenderest the purest affection – I would undergo any hardships to be near you and you will not lett me – suppose this campaign should be like the last carried into the winter – do you intend not to see me in all that time – tell me dear what your plan is –

I wrote you that the Hero Sailed while I was at Newburg – She did but has been cruiseing about from harbour to harbour since – to get met – she is now here, and will sail in a day or two for france –

I wish I had fifty guinies to spare to send by her for necessarys – but I have not – the very little gold we have must be reserved for my Love in case he should be taken – for friends in such a case are not too common. – I am more distressed from the hott weather than any other fears – God grant you may not go farther south’ard – if you should I possitively will come too – I believe Genl Howe is a paltry fellow – but happy for as that he is so – are you not much pleased with the news from the Northard we think it is a great affair and a confirmation of St Clairs villainy baseness – I hope he will not go unpunished – we hear also that Genl Gates is to go back to his command. – if so Master Schuyler, cannot be guiltless – it is very strange, you never mentioned that affair in any of your letters –

What has become of Mrs Greene, do you all live together – or how do you manage – is Billy to remain with you payless or is he to have a commission – if the former I think he had much better remained where he was – if he understood business he might without a capital have made a fortune – people here – without advanceing a shilling frequently clear hundreds in a day – such chaps as Eben Oliver – are all men of fortune – while persons – who have ever lived in affluence – are in danger of want – oh that you had less of the military man about you – you might then after the war have lived at ease all the days of your life – but now I don't know what you will do – your being long acustomed to command – will make you too haughty for mercantile matters – tho I hope you will not consider yourself as commander in chief of your own house – but be convinced tho not in the affair of Mr Coudre that there is such a thing as equal command – I send this by Capt Randal who says he expects to remain with you – pray how many of these lads have have you – I am sure they must be very expensive – I am in want of some square dollars – which I expect from you to by me a peace of linen an article I can do no longer without haveing had no recruit of that kind for almost five years – girls in general when they marry are well stocked with those things but poor I had no such advantage –

little Lucy who is without exception the sweetest child in the world – sends you a kiss but where shall I take it from say you – from the paper I hope – but dare I say I sometimes fear that a long absence the force of bad example may lead you to forget me at sometimes – to know that it ever gave you pleasure to be in company with the finest woman in the world, would be worse than death to me – but it is not so, my Harry is too just too delicate too sincere – and too fond of his Lucy to admit the most remote thought of that distracting kind – away with it – don’t be angry with me my Love – I am not jealous of your affection – I love you with a love as true and sacred as ever entered the human heart – but from a diffidence of my own merit I sometimes fear you will Love me less – after being so long from me – if you should may my life end before I know it – that I may die thinking you wholly mine –

Adieu my love

LK

Source: Lucy Flucker Knox to Henry Knox, August 23, 1777, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC02437.00638.

Excerpt

Excerpt from a Letter from Lucy Knox to Henry Knox, August 23, 1777

My Dearest Friend —

. . . When I seriously reflect that I have lost my father, mother, brother, and sisters—entirely lost them—I am half distracted, true. I cheerfully resigned them for one far dearer to me than all of them, but I am totally deprived of him—I have not seen him for almost six months—and he writes me without pointing out any method by which I may ever expect to see him again. ’Tis hard, my Harry, indeed it is. I love you with the tenderest, the purest affection. I would undergo any hardships to be near you, and you will not let me. Suppose this campaign should be like the last, carried into the winter. Do you intend not to see me in all that time? Tell me, dear, what your plan is.

Oh, that you had less of the military man about you! You might then, after the war, have lived at ease all the days of your life. But now I don't know what you will do. Your being long accustomed to command will make you too haughty for mercantile matters, though I hope you will not consider yourself as commander in chief of your own house, but be convinced that there is such a thing as equal command.

I love you with a love as true and sacred as ever entered the human heart. But from a diffidence of my own merit I sometimes fear you will love me less after being so long from me. If you should, may my life end before I know it, that I may die thinking you wholly mine. . . .

Source: Lucy Flucker Knox to Henry Knox, August 23, 1777, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC02437.00638.