James Madison’s Plan for a National Government, 1787

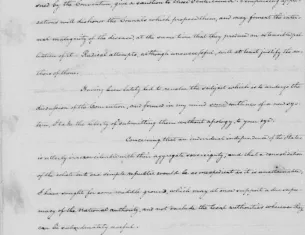

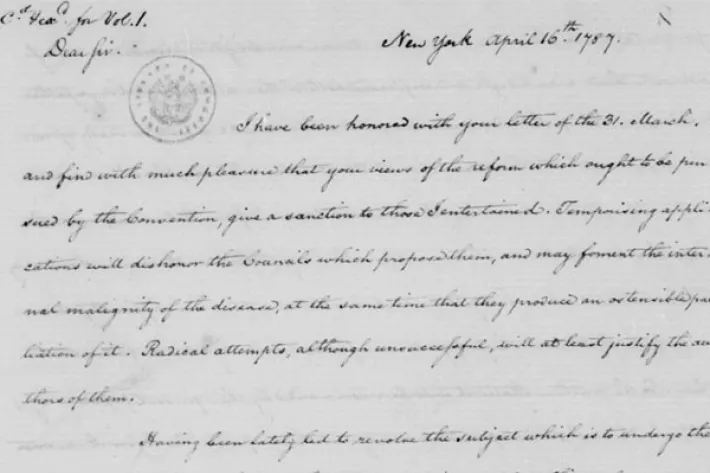

James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787 (Library of Congress)

In this letter written to George Washington a month before the Constitutional Convention, Madison lays out a detailed plan to create a government that would function on a national level while preserving some autonomy for the states. Well aware that larger, powerful states like Massachusetts and Virginia could dominate most national plans, Madison muses on the role of state legislatures in a national process, which in turn leads him to consider the supremacy of national over state judiciaries.

A Letter from James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787

New York April 16 1787

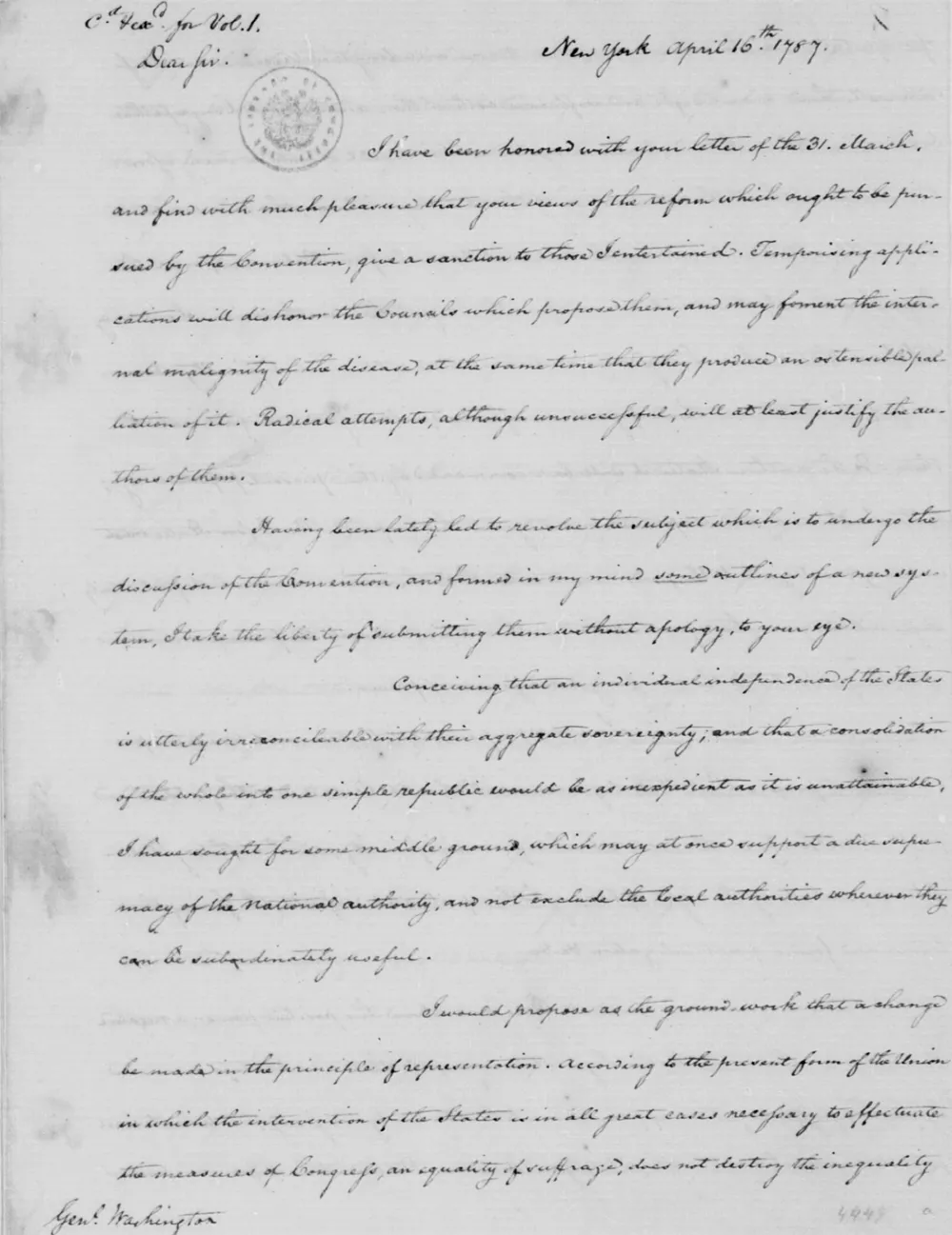

I have been honoured with your letter of the 31 of March, and find with much pleasure that your views of the reform which ought to be pursued by the Convention, give a sanction to those which I have entertained. Temporising applications will dishonor the Councils which propose them, and may foment the internal malignity of the disease, at the same time that they produce an ostensible palliation of it. Radical attempts, although unsuccessful, will at least justify the authors of them. Having been lately led to revolve the subject which is to undergo the discussion of the Convention, and formed in my mind some outlines of a new system, I take the liberty of submitting them without apology, to your eye. Conceiving that an individual independence of the States is utterly irreconcileable with their aggregate sovereignty; and that a consolidation of the whole into one simple republic would be as inexpedient as it is unattainable, I have sought for some middle ground, which may at once support a due supremacy of the national authority, and not exclude the local authorities wherever they can be subordinately useful.

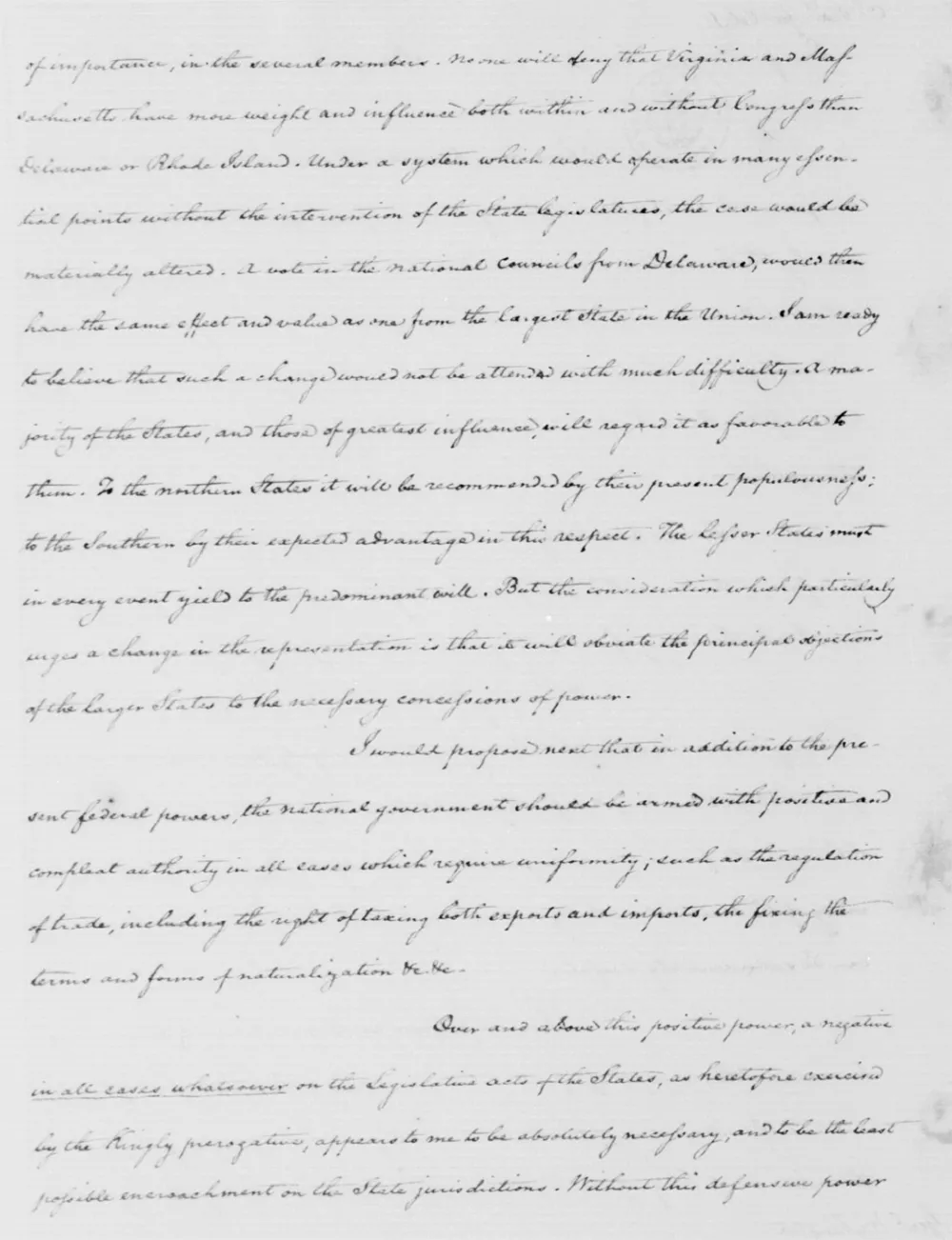

I would propose as the ground-work that a change be made in the principle of representation. According to the present form of the Union in which the intervention of the States is in all great cases necessary to effectuate the measures of Congress, an equality of suffrage, does not destroy the inequality of importance, in the several members. No one will deny that Virginia and Massts. have more weight and influence both within & without Congress than Delaware or Rho. Island. Under a system which would operate in many essential points without the intervention of the State legislatures, the case would be materially altered. A vote in the national Councils from Delaware, would then have the same effect and value as one from the largest State in the Union. I am ready to believe that such a change would not be attended with much difficulty. A majority of the States, and those of greatest influence, will regard it as favorable to them. To the Northern States it will be recommended by their present populousness; to the Southern by their expected advantage in this respect. The lesser States must in every event yield to the predominant will. But the consideration which particularly urges a change in the representation is that it will obviate the principal objections of the larger States to the necessary concessions of power.

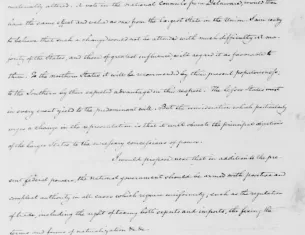

I would propose next that in addition to the present federal powers, the national Government should be armed with positive and compleat authority in all cases which require uniformity; such as the regulation of trade, including the right of taxing both exports & imports, the fixing the terms and forms of naturalization, &c &c. Over and above this positive power, a negative in all cases whatsoever on the legislative acts of the States, as heretofore exercised by the Kingly prerogative, appears to me to be absolutely necessary, and to be the least possible encroachment on the State jurisdictions. Without this defensive power, every positive power that can be given on paper will be evaded & defeated. The States will continue to invade the national jurisdiction, to violate treaties and the law of nations & to harrass each other with rival and spiteful measures dictated by mistaken views of interest. Another happy effect of this prerogative would be its controul on the internal vicisitudes of State policy; and the aggressions of interested majorities on the rights of minorities and of individuals. The great desideratum which has not yet been found for Republican Governments, seems to be some disinterested & dispassionate umpire in disputes between different passions & interests in the State. The majority who alone have the right of decision, have frequently an interest real or supposed in abusing it. In Monarchies the sovereign is more neutral to the interests and views of different parties; but unfortunately he too often forms interests of his own repugnant to those of the whole. Might not the national prerogative here suggested be found sufficiently disinterested for the decision of local questions of policy, whilst it would itself be sufficiently restrained from the pursuit of interests adverse to those of the whole Society? There has not been any moment since the peace at which the representatives of the union would have given an assent to paper money or any other measure of a kindred nature.

The national supremacy ought also to be extended as I conceive to the Judiciary departments. If those who are to expound & apply the laws, are connected by their interests & their oaths with the particular States wholly, and not with the Union, the participation of the Union in the making of the laws may be possibly rendered unavailing. It seems at least necessary that the oaths of the Judges should include a fidelity to the general as well as local constitution, and that an appeal should lie to some national tribunals in all cases to which foreigners or inhabitants of other States may be parties. The admiralty jurisdiction seems to fall entirely within the purview of the national Government. The national supremacy in the Executive departments is liable to some difficulty, unless the officers administering them could be made appointable by the supreme Government. The Militia ought certainly to be placed in some form or other under the authority which is entrusted with the general protection and defence.

A Government composed of such extensive powers should be well organized and balanced. The Legislative department might be divided into two branches; one of them chosen every years by the people at large, or by the legislatures; the other to consist of fewer members, to hold their places for a longer term, and to go out in such a rotation as always to leave in office a large majority of old members. Perhaps the negative on the laws might be most conveniently exercised by this branch. As a further check, a council of revision including the great ministerial officers might be superadded. A national Executive must also be provided. I have scarcely ventured as yet to form my own opinion either of the manner in which it ought to be constituted or of the authorities with which it ought to be cloathed. An article should be inserted expressly guarantying the tranquillity of the States against internal as well as external dangers. In like manner the right of coercion should be expressly declared. With the resources of Commerce in hand, the national administration might always find means of exerting it either by sea or land; But the difficulty & awkwardness of operating by force on the collective will of a State, render it particularly desirable that the necessity of it might be precluded. Perhaps the negative on the laws might create such a mutuality of dependence between the General and particular authorities, as to answer this purpose. Or perhaps some defined objects of taxation might be submitted along with commerce, to the general authority.

To give a new System its proper validity and energy, a ratification must be obtained from the people, and not merely from the ordinary authority of the Legislatures. This will be the more essential as inroads on the existing Constitutions of the States will be unavoidable. The inclosed address to the States on the subject of the Treaty of peace has been agreed to by Congress, & forwarded to the several Executives.

1 We foresee the irritation which it will excite in many of our Countrymen; but could not withold our approbation of the measure. Both, the resolutions and the address, passed without a dissenting voice. Congress continue to be thin, and of course do little business of importance. The settlement of the public accounts, the disposition of the public lands, and arrangements with Spain, are subjects which claim their particular attention. As a step towards the first, the treasury board are charged with the task of reporting a plan by which the final decision on the claims of the States will be handed over from Congress to a select set of men bound by the oaths, and cloathed with the powers, of Chancellors. As to the Second article, Congress have it themselves under consideration. Between 6 & 700 thousand acres have been surveyed and are ready for sale.

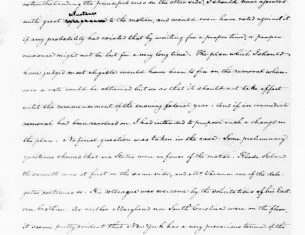

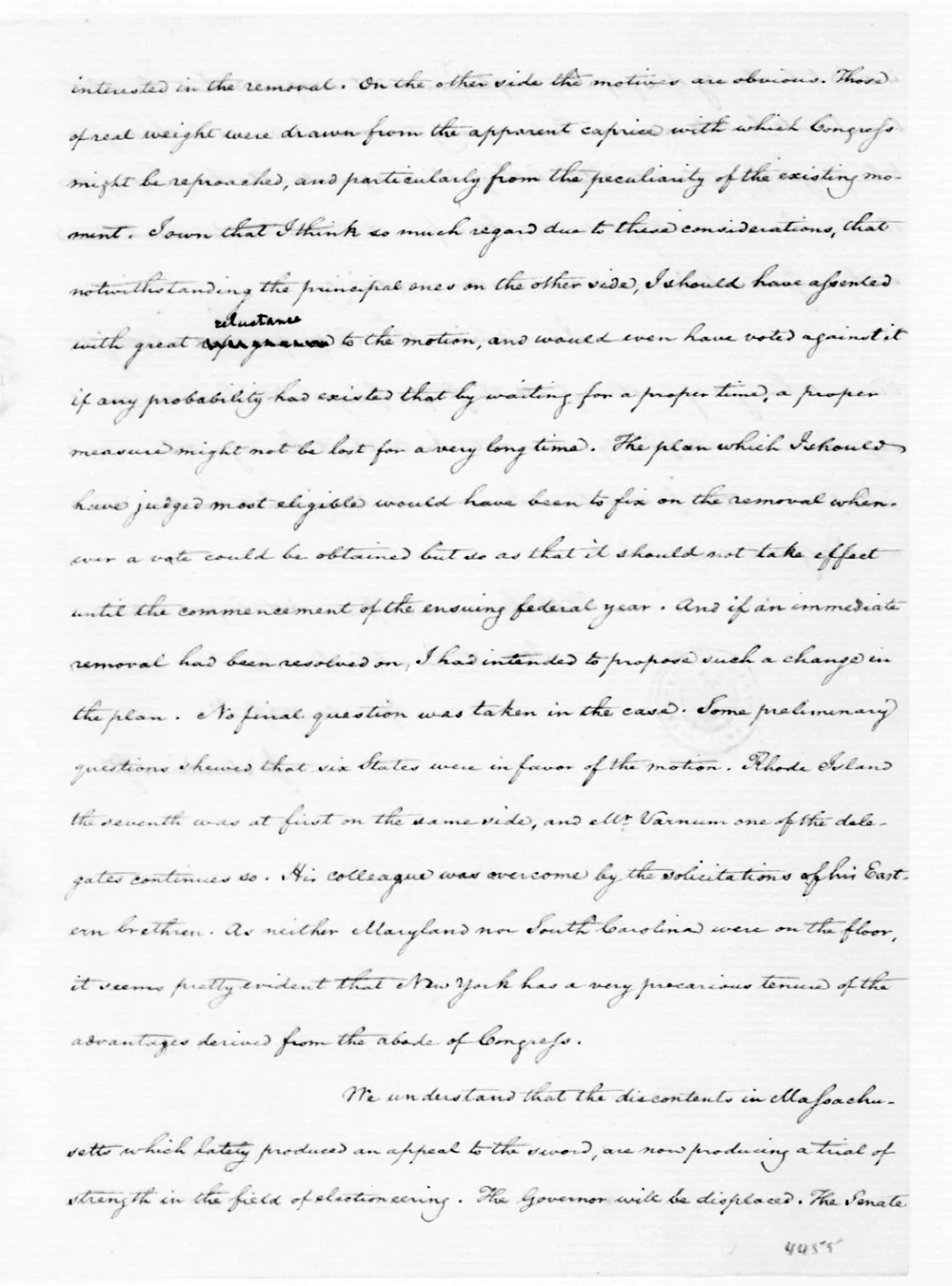

2 The mode of sale however will probably be a source of different opinions; as will the mode of disposing of the unsurveyed residue. The Eastern gentlemen remain attached to the scheme of townships. Many others are equally strenuous for indiscriminate locations. The States which have lands of their own for sale, are suspected of not being hearty in bringing the federal lands to market. The business with Spain is becoming extremely delicate, and the information from the Western settlements truly alarming. A motion was made some days ago for an adjournment of Congress for a short period, and an appointment of Philada. for their reassembling. The excentricity of this place as well with regard to E. and West as to N. & South has I find been for a considerable time a thorn in the minds of many of the Southern members. Suspicion too has charged some important votes on the weight thrown by the present position of Congress into the Eastern Scale, and predicts that the Eastern members will never concur in any substantial provision or movement for a proper permanent seat for the national Government whilst they remain so much gratified in its temporary residence. These seem to have been the operative motives with those on one side who were not locally interested in the removal. On the other side the motives are obvious. Those of real weight were drawn from the apparent caprice with which Congress might be reproached, and particularly from the peculiarity of the existing moment. I own that I think so much regard due to these considerations, that notwithstanding the powerful ones on the other side, I should have assented with great repugnance to the motion, and would even have voted against it if any probability had existed that by waiting for a proper time, a proper measure might not be lost for a very long time. The plan which I shd. have judged most eligible would have been to fix on the removal whenever a vote could be obtained but so as that it should not take effect until the commencement of the ensuing federal year. And if an immediate removal had been resolved on, I had intended to propose such a change in the plan. No final question was taken in the case. Some preliminary questions shewed that six States were in favor of the motion. Rho. Island the 7th. was at first on the same side, and Mr. Varnum one of her delegates continues so. His colleague was overcome by the solicitations of his Eastern brethren. As neither Maryland nor South Carolina were on the floor, it seems pretty evident that N. York has a very precarious tenure of the advantages derived from the abode of Congress. We understand that the discontents in Massts which lately produced an appeal to the sword, are now producing a trial of strength in the field of electioneering. The Governor will be displaced. The Senate is said to be already of a popular complexion, and it is expected the other branch will be still more so. Paper money it is surmised will be the engine to be played off agst. creditors both public and private. As the event of the Elections however is not yet decided, this information must be too much blended with conjecture to be regarded as matter of certainty. I do not learn that the proposed act relating to Vermont has yet gone through all the stages of legislation here; nor can I say whether it will finally pass or not. In truth, it having not been a subject of conversation for some time, I am unable to say what has been done or is likely to be done with it. With the sincerest affection & the highest esteem I have the honor to be Dear Sir

Your devoted Servt.

Js. Madison Jr

Source: James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787, The James Madison Papers at the Library of Congress.

A Letter from James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787

New York April 16 1787

Dear Sir

I have been honoured with your letter of the 31 of March, and find with much pleasure that your views of the reform which ought to be pursued by the Convention . . . Having been lately led to revolve the subject which is to undergo the discussion of the Convention, and formed in my mind some outlines of a new system, I take the liberty of submitting them without apology, to your eye . . .

I would propose as the ground-work that a change be made in the principle of representation. According to the present form of the Union . . . No one will deny that Virginia and Massts. have more weight and influence both within & without Congress than Delaware or Rho. Island. Under a system which would operate in many essential points without the intervention of the State legislatures . . . The lesser States must in every event yield to the predominant will . . .

I would propose next that in addition to the present federal powers, the national Government should be armed with positive and compleat authority in all cases which require uniformity . . . The States will continue to invade the national jurisdiction, to violate treaties and the law of nations & to harrass each other with rival and spiteful measures . . .

The national supremacy ought also to be extended as I conceive to the Judiciary departments. . . . It seems at least necessary that the oaths of the Judges should include a fidelity to the general as well as local constitution . . .

A Government composed of such extensive powers should be well organized and balanced. The Legislative department might be divided into two branches; one of them chosen every years by the people at large, or by the legislatures; the other to consist of fewer members, to hold their places for a longer term, and to go out in such a rotation as always to leave in office a large majority of old members . . .

To give a new System its proper validity and energy, a ratification must be obtained from the people, and not merely from the ordinary authority of the Legislatures. This will be the more essential as inroads on the existing Constitutions of the States will be unavoidable . . .

With the sincerest affection & the highest esteem I have the honor to be Dear Sir Your devoted Servt.

Js. Madison Jr

Source: James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787, The James Madison Papers at the Library of Congress.

A Letter from James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787

New York April 16 1787

Dear Sir

. . . Having been lately led to revolve the subject which is to undergo the discussion of the Convention. . . .

I would propose as the ground-work that a change be made in the principle of representation. According to the present form of the Union . . . No one will deny that Virginia and Massts. have more weight and influence both within & without Congress than Delaware or Rho. Island. . . . The lesser States must in every event yield to the predominant will. . . .

A Government composed of such extensive powers should be well organized and balanced. The Legislative department might be divided into two branches; one of them chosen every years by the people at large, or by the legislatures. . . .

Sir Your devoted Servt.

Js. Madison Jr

Source: James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787, The James Madison Papers at the Library of Congress.

Background

In this letter written to George Washington a month before the Constitutional Convention, Madison lays out a detailed plan to create a government that would function on a national level while preserving some autonomy for the states. Well aware that larger, powerful states like Massachusetts and Virginia could dominate most national plans, Madison muses on the role of state legislatures in a national process, which in turn leads him to consider the supremacy of national over state judiciaries.

Transcript

A Letter from James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787

New York April 16 1787

I have been honoured with your letter of the 31 of March, and find with much pleasure that your views of the reform which ought to be pursued by the Convention, give a sanction to those which I have entertained. Temporising applications will dishonor the Councils which propose them, and may foment the internal malignity of the disease, at the same time that they produce an ostensible palliation of it. Radical attempts, although unsuccessful, will at least justify the authors of them. Having been lately led to revolve the subject which is to undergo the discussion of the Convention, and formed in my mind some outlines of a new system, I take the liberty of submitting them without apology, to your eye. Conceiving that an individual independence of the States is utterly irreconcileable with their aggregate sovereignty; and that a consolidation of the whole into one simple republic would be as inexpedient as it is unattainable, I have sought for some middle ground, which may at once support a due supremacy of the national authority, and not exclude the local authorities wherever they can be subordinately useful.

I would propose as the ground-work that a change be made in the principle of representation. According to the present form of the Union in which the intervention of the States is in all great cases necessary to effectuate the measures of Congress, an equality of suffrage, does not destroy the inequality of importance, in the several members. No one will deny that Virginia and Massts. have more weight and influence both within & without Congress than Delaware or Rho. Island. Under a system which would operate in many essential points without the intervention of the State legislatures, the case would be materially altered. A vote in the national Councils from Delaware, would then have the same effect and value as one from the largest State in the Union. I am ready to believe that such a change would not be attended with much difficulty. A majority of the States, and those of greatest influence, will regard it as favorable to them. To the Northern States it will be recommended by their present populousness; to the Southern by their expected advantage in this respect. The lesser States must in every event yield to the predominant will. But the consideration which particularly urges a change in the representation is that it will obviate the principal objections of the larger States to the necessary concessions of power.

I would propose next that in addition to the present federal powers, the national Government should be armed with positive and compleat authority in all cases which require uniformity; such as the regulation of trade, including the right of taxing both exports & imports, the fixing the terms and forms of naturalization, &c &c. Over and above this positive power, a negative in all cases whatsoever on the legislative acts of the States, as heretofore exercised by the Kingly prerogative, appears to me to be absolutely necessary, and to be the least possible encroachment on the State jurisdictions. Without this defensive power, every positive power that can be given on paper will be evaded & defeated. The States will continue to invade the national jurisdiction, to violate treaties and the law of nations & to harrass each other with rival and spiteful measures dictated by mistaken views of interest. Another happy effect of this prerogative would be its controul on the internal vicisitudes of State policy; and the aggressions of interested majorities on the rights of minorities and of individuals. The great desideratum which has not yet been found for Republican Governments, seems to be some disinterested & dispassionate umpire in disputes between different passions & interests in the State. The majority who alone have the right of decision, have frequently an interest real or supposed in abusing it. In Monarchies the sovereign is more neutral to the interests and views of different parties; but unfortunately he too often forms interests of his own repugnant to those of the whole. Might not the national prerogative here suggested be found sufficiently disinterested for the decision of local questions of policy, whilst it would itself be sufficiently restrained from the pursuit of interests adverse to those of the whole Society? There has not been any moment since the peace at which the representatives of the union would have given an assent to paper money or any other measure of a kindred nature.

The national supremacy ought also to be extended as I conceive to the Judiciary departments. If those who are to expound & apply the laws, are connected by their interests & their oaths with the particular States wholly, and not with the Union, the participation of the Union in the making of the laws may be possibly rendered unavailing. It seems at least necessary that the oaths of the Judges should include a fidelity to the general as well as local constitution, and that an appeal should lie to some national tribunals in all cases to which foreigners or inhabitants of other States may be parties. The admiralty jurisdiction seems to fall entirely within the purview of the national Government. The national supremacy in the Executive departments is liable to some difficulty, unless the officers administering them could be made appointable by the supreme Government. The Militia ought certainly to be placed in some form or other under the authority which is entrusted with the general protection and defence.

A Government composed of such extensive powers should be well organized and balanced. The Legislative department might be divided into two branches; one of them chosen every years by the people at large, or by the legislatures; the other to consist of fewer members, to hold their places for a longer term, and to go out in such a rotation as always to leave in office a large majority of old members. Perhaps the negative on the laws might be most conveniently exercised by this branch. As a further check, a council of revision including the great ministerial officers might be superadded. A national Executive must also be provided. I have scarcely ventured as yet to form my own opinion either of the manner in which it ought to be constituted or of the authorities with which it ought to be cloathed. An article should be inserted expressly guarantying the tranquillity of the States against internal as well as external dangers. In like manner the right of coercion should be expressly declared. With the resources of Commerce in hand, the national administration might always find means of exerting it either by sea or land; But the difficulty & awkwardness of operating by force on the collective will of a State, render it particularly desirable that the necessity of it might be precluded. Perhaps the negative on the laws might create such a mutuality of dependence between the General and particular authorities, as to answer this purpose. Or perhaps some defined objects of taxation might be submitted along with commerce, to the general authority.

To give a new System its proper validity and energy, a ratification must be obtained from the people, and not merely from the ordinary authority of the Legislatures. This will be the more essential as inroads on the existing Constitutions of the States will be unavoidable. The inclosed address to the States on the subject of the Treaty of peace has been agreed to by Congress, & forwarded to the several Executives.

1 We foresee the irritation which it will excite in many of our Countrymen; but could not withold our approbation of the measure. Both, the resolutions and the address, passed without a dissenting voice. Congress continue to be thin, and of course do little business of importance. The settlement of the public accounts, the disposition of the public lands, and arrangements with Spain, are subjects which claim their particular attention. As a step towards the first, the treasury board are charged with the task of reporting a plan by which the final decision on the claims of the States will be handed over from Congress to a select set of men bound by the oaths, and cloathed with the powers, of Chancellors. As to the Second article, Congress have it themselves under consideration. Between 6 & 700 thousand acres have been surveyed and are ready for sale.

2 The mode of sale however will probably be a source of different opinions; as will the mode of disposing of the unsurveyed residue. The Eastern gentlemen remain attached to the scheme of townships. Many others are equally strenuous for indiscriminate locations. The States which have lands of their own for sale, are suspected of not being hearty in bringing the federal lands to market. The business with Spain is becoming extremely delicate, and the information from the Western settlements truly alarming. A motion was made some days ago for an adjournment of Congress for a short period, and an appointment of Philada. for their reassembling. The excentricity of this place as well with regard to E. and West as to N. & South has I find been for a considerable time a thorn in the minds of many of the Southern members. Suspicion too has charged some important votes on the weight thrown by the present position of Congress into the Eastern Scale, and predicts that the Eastern members will never concur in any substantial provision or movement for a proper permanent seat for the national Government whilst they remain so much gratified in its temporary residence. These seem to have been the operative motives with those on one side who were not locally interested in the removal. On the other side the motives are obvious. Those of real weight were drawn from the apparent caprice with which Congress might be reproached, and particularly from the peculiarity of the existing moment. I own that I think so much regard due to these considerations, that notwithstanding the powerful ones on the other side, I should have assented with great repugnance to the motion, and would even have voted against it if any probability had existed that by waiting for a proper time, a proper measure might not be lost for a very long time. The plan which I shd. have judged most eligible would have been to fix on the removal whenever a vote could be obtained but so as that it should not take effect until the commencement of the ensuing federal year. And if an immediate removal had been resolved on, I had intended to propose such a change in the plan. No final question was taken in the case. Some preliminary questions shewed that six States were in favor of the motion. Rho. Island the 7th. was at first on the same side, and Mr. Varnum one of her delegates continues so. His colleague was overcome by the solicitations of his Eastern brethren. As neither Maryland nor South Carolina were on the floor, it seems pretty evident that N. York has a very precarious tenure of the advantages derived from the abode of Congress. We understand that the discontents in Massts which lately produced an appeal to the sword, are now producing a trial of strength in the field of electioneering. The Governor will be displaced. The Senate is said to be already of a popular complexion, and it is expected the other branch will be still more so. Paper money it is surmised will be the engine to be played off agst. creditors both public and private. As the event of the Elections however is not yet decided, this information must be too much blended with conjecture to be regarded as matter of certainty. I do not learn that the proposed act relating to Vermont has yet gone through all the stages of legislation here; nor can I say whether it will finally pass or not. In truth, it having not been a subject of conversation for some time, I am unable to say what has been done or is likely to be done with it. With the sincerest affection & the highest esteem I have the honor to be Dear Sir

Your devoted Servt.

Js. Madison Jr

Source: James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787, The James Madison Papers at the Library of Congress.

Excerpt

A Letter from James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787

New York April 16 1787

Dear Sir

I have been honoured with your letter of the 31 of March, and find with much pleasure that your views of the reform which ought to be pursued by the Convention . . . Having been lately led to revolve the subject which is to undergo the discussion of the Convention, and formed in my mind some outlines of a new system, I take the liberty of submitting them without apology, to your eye . . .

I would propose as the ground-work that a change be made in the principle of representation. According to the present form of the Union . . . No one will deny that Virginia and Massts. have more weight and influence both within & without Congress than Delaware or Rho. Island. Under a system which would operate in many essential points without the intervention of the State legislatures . . . The lesser States must in every event yield to the predominant will . . .

I would propose next that in addition to the present federal powers, the national Government should be armed with positive and compleat authority in all cases which require uniformity . . . The States will continue to invade the national jurisdiction, to violate treaties and the law of nations & to harrass each other with rival and spiteful measures . . .

The national supremacy ought also to be extended as I conceive to the Judiciary departments. . . . It seems at least necessary that the oaths of the Judges should include a fidelity to the general as well as local constitution . . .

A Government composed of such extensive powers should be well organized and balanced. The Legislative department might be divided into two branches; one of them chosen every years by the people at large, or by the legislatures; the other to consist of fewer members, to hold their places for a longer term, and to go out in such a rotation as always to leave in office a large majority of old members . . .

To give a new System its proper validity and energy, a ratification must be obtained from the people, and not merely from the ordinary authority of the Legislatures. This will be the more essential as inroads on the existing Constitutions of the States will be unavoidable . . .

With the sincerest affection & the highest esteem I have the honor to be Dear Sir Your devoted Servt.

Js. Madison Jr

Source: James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787, The James Madison Papers at the Library of Congress.

Excerpt 100

A Letter from James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787

New York April 16 1787

Dear Sir

. . . Having been lately led to revolve the subject which is to undergo the discussion of the Convention. . . .

I would propose as the ground-work that a change be made in the principle of representation. According to the present form of the Union . . . No one will deny that Virginia and Massts. have more weight and influence both within & without Congress than Delaware or Rho. Island. . . . The lesser States must in every event yield to the predominant will. . . .

A Government composed of such extensive powers should be well organized and balanced. The Legislative department might be divided into two branches; one of them chosen every years by the people at large, or by the legislatures. . . .

Sir Your devoted Servt.

Js. Madison Jr

Source: James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787, The James Madison Papers at the Library of Congress.