George III Addresses Parliament on the Rebellion, 1775

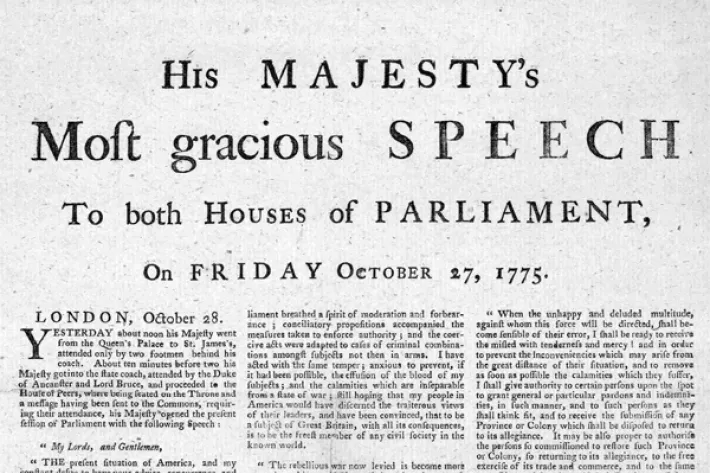

His Majesty's Most Gracious Speech to Both Houses of Parliament, on Friday, October 27, 1775 (Library of Congress)

King George III addressed Parliament to declare that Great Britain would not give independence to the colonies and to discuss his concerns about the growing rebellion.

King George’s Address to Parliament, October 27, 1775

His MAJESTY’s

Most gracious SPEECH

to both Houses of PARLIAMENT,

on FRIDAY, October 27, 1775.

LONDON, October 28.

YESTERDAY about noon his Majesty went from the Queen’s Palace to St. James’s, attended only by two footmen behind his coach. About ten minutes before two his Majesty got into the state coach, attended by the Duke of Anccanster and Lord Bruce, and proceeded to the House of Peers, where being seated on the Throne and a message having been sent to the Commons, requiring their attendance, his Majesty opened the present session of Parliment with the following Speech:

“ My Lords, and Gentlemen,

"THE present situation of America, and my constant desire to have your advice, concurrence, and assistance on every important occasion, have determined me to call you thus early together.

"Those who have long too successfully laboured to inflame my people in America by gross misrepresentations, and to infuse into their minds a system of opinions repugnant to the true constitution of the colonies, and to their subordinate relation to Great-Britain, now openly avow their revolt, hostility, and rebellion. They have raised troops, and are collecting a naval force; they have seized the public revenue, and assumed to themselves legislative, executive, and judicial powers, which they already exercise in the most arbitrary manner, over the persons and property of their fellow-subjects: And although many of these unhappy people may still retain their loyalty, and may be too wise not to see the fatal consequence of this usurpation, and wish to resist it, yet the torrent of violence has been strong enough to compel their acquiescence, till a sufficient force shall appear to support them.

"The authors and promoters of this desperate conspiracy have, in the conduct of it, derived great advantage from the difference of our intentions and theirs. They meant only to amuse by vague expressions of attachment to the Parent State, and the strongest protestations of loyalty to me, whilst they were preparing for a general revolt. On our part, though it was declared in your last session that a rebellion existed within the province of the Massachusetts Bay; yet even that province we wished rather to reclaim than to subdue. The resolutions of Parliament breathed a spirit of moderation and forbearance; conciliatory propositions accompanied the measures taken to enforce authority; and the coercive acts were adapted to cases of criminal combinations amongst subjects not then in arms. I have acted with the same temper; anxious to prevent, if it had been possible, the effusion of the blood of my subjects; and the calamities which are inseparable from a state of war; still hoping that my people in America would have discerned the traiterous views of their leaders, and have been convinced, that to be a subject of Great Britain, with all its consequences, is to be the freest member of any civil society in the known world.

"The rebellious war now levied is become more general, and is manifestly carried on for the purpose of establishing an independent empire. I need not dwell upon the fatal effects of the success of such a plan. The object is too important, the spirit of the British nation too high, the resources with which God hath blessed her too numerous, to give up so many colonies which she has planted with great industry, nursed with great tenderness, encouraged with many commercial advantages, and protected and defended at much expence of blood and treasure.

"It is now become the part of wisdom, and (in its effects) of clemency, to put a speedy end to these disorders by the most decisive exertions. For this purpose, I have increased my naval establishment, and greatly augmented my land forces; but in such a manner as may be the least burthensome to my kingdoms.

"I have also the satisfaction to inform you, that I have received the most friendly offers of foreign assistance; and if I shall make any treaties in consequence thereof, they shall be laid before you. And I have, in testimony of my affection for my people, who can have no cause in which I am not equally interested, sent to the garrisons of Gibraltar and Port-Mahon a part of my Electoral troops, in order that a larger number of the established forces of this kingdom may be applied to the maintenance of its authority; and the national militia, planned and regulated with equal regard to the rights, safety and protection of my crown and people, may give a farther extent and activity to our military operations.

"When the unhappy and deluded multitude, against whom this force will be directed, shall become sensible of their error, I shall be ready to receive the misled with tenderness and mercy ! and in order to prevent the inconveniencies which may arise from the great distance of their situation, and to remove as soon as possible the calamities which they suffer, I shall give authority to certain persons upon the spot to grant general or particular pardons and indemnities, in such manner, and to such persons as they shall think fit; and to receive the submission of any Province or Colony which shall be disposed to return to its allegiance. It may be also proper to authorise the persons so commissioned to restore such Province or Colony, so returning to its allegiance, to the free exercise of its trade and commerce, and to the same protection and security as if such Province or Colony had never revolted.

"Gentlemen of the House of Commons,

"I have ordered the proper estimates for the ensuing year to be laid before you; and I rely on your affection to me, and your resolution to maintain the just rights of this country, for such supplies as the present circumstances of our affairs require. Among the many unavoidable ill consequences of this rebellion, none affects me more sensibly than the extraordinary burthen which it must create to my faithful subjects.

"My Lords, and Gentlemen,

"I have fully opened to you my views and intentions. The constant employment of my thoughts, and the most earnest wishes of my heart, tend wholly to the safety and happiness of all my people, and to the re-establishment of order and tranquility through the several parts of my dominions, in a close connection and constitutional dependance. You see the tendency of the present disorders, and I have stated to you the measures which I mean to pursue for suppressing them. Whatever remains to be done, that may farther contribute to this end, I commit to your wisdom. And I am happy to add, that, as well from the assurances I have received, as from the general appearances of affairs in Europe, I see no probability that the measures which you may adopt will be interrupted by disputes with any foreign power."

Source: Library of Congress

King George’s Address to Parliament, October 27, 1775

His MAJESTY’s

Most gracious SPEECH

to both Houses of PARLIMENT,

on FRIDAY, October 27, 1775.

LONDON, October 28.

"My Lords, and Gentlemen,

"THE present situation of America . . . determined me to call you . . .

"Those who have long too successfully laboured to inflame my people in America . . . now openly avow their revolt, hostility, and rebellion. They have raised troops, and are collecting a naval force; they have seized the public revenue, and assumed to themselves legislative, executive, and judicial powers . . .

"The authors and promoters of this desperate conspiracy . . . meant only to amuse by vague expressions of attachment to the Parent State . . . whilst they were preparing for a general revolt . . . The resolutions of Parliament breathed a spirit of moderation . . . and the coercive acts were adapted to cases of criminal combinations amongst subjects not then in arms. I have acted with the same temper; anxious to prevent, if it had been possible, the effusion of the blood of my subjects . . . still hoping that my people in America would have . . . been convinced, that to be a subject of Great Britain . . . is to be the freest member of any civil society in the known world.

"The rebellious war now levied is become more general . . . the purpose of establishing an independent empire. I need not dwell upon the fatal effects of the success of such a plan. The object is too important . . . the resources with which God hath blessed her too numerous, to give up so many colonies which she has planted with great industry, nursed with great tenderness, encouraged with many commercial advantages, and protected and defended at much expence of blood and treasure . . .

"When the unhappy and deluded multitude, against whom this force will be directed, shall become sensible of their error, I shall be ready to receive the misled with tenderness and mercy . . . so returning to its allegiance, to the free exercise of its trade and commerce, and to the same protection and security as if such Province or Colony had never revolted . . .

Source: Library of Congress

avow - confess openly

coercive - relating to or using force or threats

effusion - outpouring

levied - imposed

multitude - a large number

allegiance - loyalty

Background

King George III addressed Parliament to declare that Great Britain would not give independence to the colonies and to discuss his concerns about the growing rebellion.

Transcript

King George’s Address to Parliament, October 27, 1775

His MAJESTY’s

Most gracious SPEECH

to both Houses of PARLIAMENT,

on FRIDAY, October 27, 1775.

LONDON, October 28.

YESTERDAY about noon his Majesty went from the Queen’s Palace to St. James’s, attended only by two footmen behind his coach. About ten minutes before two his Majesty got into the state coach, attended by the Duke of Anccanster and Lord Bruce, and proceeded to the House of Peers, where being seated on the Throne and a message having been sent to the Commons, requiring their attendance, his Majesty opened the present session of Parliment with the following Speech:

“ My Lords, and Gentlemen,

"THE present situation of America, and my constant desire to have your advice, concurrence, and assistance on every important occasion, have determined me to call you thus early together.

"Those who have long too successfully laboured to inflame my people in America by gross misrepresentations, and to infuse into their minds a system of opinions repugnant to the true constitution of the colonies, and to their subordinate relation to Great-Britain, now openly avow their revolt, hostility, and rebellion. They have raised troops, and are collecting a naval force; they have seized the public revenue, and assumed to themselves legislative, executive, and judicial powers, which they already exercise in the most arbitrary manner, over the persons and property of their fellow-subjects: And although many of these unhappy people may still retain their loyalty, and may be too wise not to see the fatal consequence of this usurpation, and wish to resist it, yet the torrent of violence has been strong enough to compel their acquiescence, till a sufficient force shall appear to support them.

"The authors and promoters of this desperate conspiracy have, in the conduct of it, derived great advantage from the difference of our intentions and theirs. They meant only to amuse by vague expressions of attachment to the Parent State, and the strongest protestations of loyalty to me, whilst they were preparing for a general revolt. On our part, though it was declared in your last session that a rebellion existed within the province of the Massachusetts Bay; yet even that province we wished rather to reclaim than to subdue. The resolutions of Parliament breathed a spirit of moderation and forbearance; conciliatory propositions accompanied the measures taken to enforce authority; and the coercive acts were adapted to cases of criminal combinations amongst subjects not then in arms. I have acted with the same temper; anxious to prevent, if it had been possible, the effusion of the blood of my subjects; and the calamities which are inseparable from a state of war; still hoping that my people in America would have discerned the traiterous views of their leaders, and have been convinced, that to be a subject of Great Britain, with all its consequences, is to be the freest member of any civil society in the known world.

"The rebellious war now levied is become more general, and is manifestly carried on for the purpose of establishing an independent empire. I need not dwell upon the fatal effects of the success of such a plan. The object is too important, the spirit of the British nation too high, the resources with which God hath blessed her too numerous, to give up so many colonies which she has planted with great industry, nursed with great tenderness, encouraged with many commercial advantages, and protected and defended at much expence of blood and treasure.

"It is now become the part of wisdom, and (in its effects) of clemency, to put a speedy end to these disorders by the most decisive exertions. For this purpose, I have increased my naval establishment, and greatly augmented my land forces; but in such a manner as may be the least burthensome to my kingdoms.

"I have also the satisfaction to inform you, that I have received the most friendly offers of foreign assistance; and if I shall make any treaties in consequence thereof, they shall be laid before you. And I have, in testimony of my affection for my people, who can have no cause in which I am not equally interested, sent to the garrisons of Gibraltar and Port-Mahon a part of my Electoral troops, in order that a larger number of the established forces of this kingdom may be applied to the maintenance of its authority; and the national militia, planned and regulated with equal regard to the rights, safety and protection of my crown and people, may give a farther extent and activity to our military operations.

"When the unhappy and deluded multitude, against whom this force will be directed, shall become sensible of their error, I shall be ready to receive the misled with tenderness and mercy ! and in order to prevent the inconveniencies which may arise from the great distance of their situation, and to remove as soon as possible the calamities which they suffer, I shall give authority to certain persons upon the spot to grant general or particular pardons and indemnities, in such manner, and to such persons as they shall think fit; and to receive the submission of any Province or Colony which shall be disposed to return to its allegiance. It may be also proper to authorise the persons so commissioned to restore such Province or Colony, so returning to its allegiance, to the free exercise of its trade and commerce, and to the same protection and security as if such Province or Colony had never revolted.

"Gentlemen of the House of Commons,

"I have ordered the proper estimates for the ensuing year to be laid before you; and I rely on your affection to me, and your resolution to maintain the just rights of this country, for such supplies as the present circumstances of our affairs require. Among the many unavoidable ill consequences of this rebellion, none affects me more sensibly than the extraordinary burthen which it must create to my faithful subjects.

"My Lords, and Gentlemen,

"I have fully opened to you my views and intentions. The constant employment of my thoughts, and the most earnest wishes of my heart, tend wholly to the safety and happiness of all my people, and to the re-establishment of order and tranquility through the several parts of my dominions, in a close connection and constitutional dependance. You see the tendency of the present disorders, and I have stated to you the measures which I mean to pursue for suppressing them. Whatever remains to be done, that may farther contribute to this end, I commit to your wisdom. And I am happy to add, that, as well from the assurances I have received, as from the general appearances of affairs in Europe, I see no probability that the measures which you may adopt will be interrupted by disputes with any foreign power."

Source: Library of Congress

Excerpt

King George’s Address to Parliament, October 27, 1775

His MAJESTY’s

Most gracious SPEECH

to both Houses of PARLIMENT,

on FRIDAY, October 27, 1775.

LONDON, October 28.

"My Lords, and Gentlemen,

"THE present situation of America . . . determined me to call you . . .

"Those who have long too successfully laboured to inflame my people in America . . . now openly avow their revolt, hostility, and rebellion. They have raised troops, and are collecting a naval force; they have seized the public revenue, and assumed to themselves legislative, executive, and judicial powers . . .

"The authors and promoters of this desperate conspiracy . . . meant only to amuse by vague expressions of attachment to the Parent State . . . whilst they were preparing for a general revolt . . . The resolutions of Parliament breathed a spirit of moderation . . . and the coercive acts were adapted to cases of criminal combinations amongst subjects not then in arms. I have acted with the same temper; anxious to prevent, if it had been possible, the effusion of the blood of my subjects . . . still hoping that my people in America would have . . . been convinced, that to be a subject of Great Britain . . . is to be the freest member of any civil society in the known world.

"The rebellious war now levied is become more general . . . the purpose of establishing an independent empire. I need not dwell upon the fatal effects of the success of such a plan. The object is too important . . . the resources with which God hath blessed her too numerous, to give up so many colonies which she has planted with great industry, nursed with great tenderness, encouraged with many commercial advantages, and protected and defended at much expence of blood and treasure . . .

"When the unhappy and deluded multitude, against whom this force will be directed, shall become sensible of their error, I shall be ready to receive the misled with tenderness and mercy . . . so returning to its allegiance, to the free exercise of its trade and commerce, and to the same protection and security as if such Province or Colony had never revolted . . .

Source: Library of Congress

avow - confess openly

coercive - relating to or using force or threats

effusion - outpouring

levied - imposed

multitude - a large number

allegiance - loyalty