The Autobiography of Richard Allen, 1833

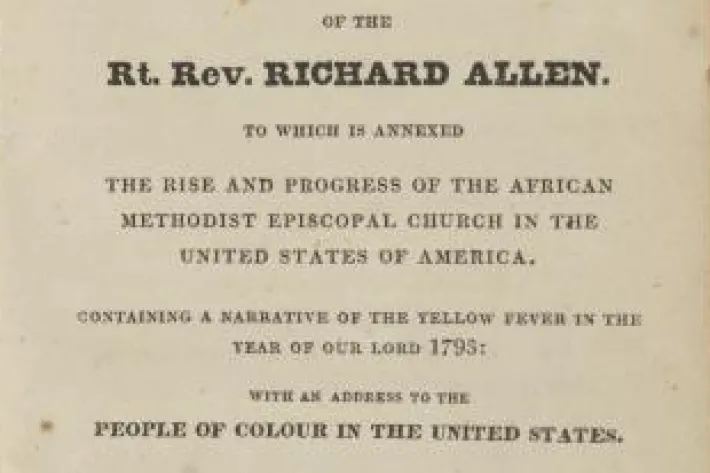

The Life, Experience, and Gospel Labours of the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen, Philadelphia: Martin & Boden, 1833

Richard Allen was born a slave in Philadelphia, and when he was still a child, his mother and three siblings were sold away from him. Allen converted to Christianity after attending Methodist church meetings and began sharing the gospel with others. Eventually, Allen and his brother were given the opportunity to purchase their own freedom. This autobiography follows his life from his childhood through the establishment of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Excerpts from Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, The Life, Experience, and Gospel Labours of the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen, 1833

I was born in the year of our Lord 1760, on February 14th, a slave to Benjamin Chew, of Philadelphia. My mother and father and four children of us were sold into Delaware State, near Dover, and I was a child and lived with him until I was upwards of twenty years of age, during which time I was awakened and brought to see myself poor, wretched and undone, and without the mercy of God must be lost. Shortly after I obtained mercy through the blood of Christ, and was constrained to exhort my old companions to seek the Lord. I went rejoicing for several days, and was happy in the Lord, in conversing with many old experienced Christians . . . I joined the Methodist society, and met in class at Benjamin Wells’s, in the forest, Delaware State . . .

My master was an unconverted man, and all the family, but he was what the world called a good master. He was more like a father to his slaves than any thing else. He was a very tender, humane man. My mother and father lived with him for many years. He was brought into difficulty, not being able to pay for us, and mother having several children after he had bought us, he sold my mother and three children. My mother sought the Lord and found favour with him, and became a very pious woman. There were three children of us remained with our old master. My oldest brother embraced religion and my sister. Our neighbours, seeing that our master indulged us with the privilege of attending meeting once in two weeks, said that Stokeley’s negroes would soon ruin him; and so my brother and myself held a council together that we would attend more faithfully to our master’s business, so that it should not be said that religion made us worse servants, we would work night and day to get our crops forward, so that they should be disappointed. We frequently went to meeting on every other Thursday; but if we were likely to be backward with our crops we would refrain from going to meeting. When our master found we were making no provision to go to meeting, he would frequently ask us if it was not our meeting day, and if we were not going. We would frequently tell him, “no, sir, we would rather stay at home and get our work done.” He would tell us, “Boys, I would rather you would go to your meeting: if I am not good myself, I like to see you striving yourselves to be good.” Our reply would be, “Thank you, sir; but we would rather stay and get our crops forward.” So we always continued to keep our crops more forward than our neighbours, and we would attend public preaching once in two weeks, and class meeting once a week. At length our master said he was convinced that religion made slaves better and not worse, and often boasted of his slaves for their honesty and industry. Some time after I asked him if I might ask the preachers to come and preach at his house. He being old and infirm, my master and mistress cheerfully agreed for me to ask some of the Methodist preachers to come and preach at his house. I asked him for a note. He replied, if my word was not sufficient, he should send no note. I accordingly asked the preacher. He seemed somewhat backward at first, as my master did not send a written request; but the class-leader (John Gray) observed that my word was sufficient; so he preached at my old master’s house on the next Wednesday. Preaching continued for some months; at length Freeborn Garrison preached from these words, “Thou art weighed in the balance, and art found wanting.” In pointing out and weighing the different characters, and among the rest weighed the slave-holders, my master believed himself to be one of that number, and after that he could not be satisfied to hold slaves, believing it to be wrong. And after that he proposed to me and my brother buying our times, to pay him sixty pounds gold and silver, or two thousand dollars continental money . . . I had it often impressed upon my mind that I should one day enjoy my freedom; for slavery is a bitter pill, notwithstanding we had a good master. But when we would think that our day’s work was never done, we often thought that after our master’s death we were liable to be sold to the highest bidder, as he was much in debt; and thus my troubles were increased, and I was often brought to weep between the porch and the altar. But I have had reason to bless my dear Lord that a door was opened unexpectedly for me to buy my time, and enjoy my liberty . . .

After peace was proclaimed I then travelled extensively, striving to preach the Gospel . . . In 1793 a committee was appointed from the African Church to solicit me to be their minister, for there was no colored preacher in Philadelphia but myself. I told them I could not accept of their offer, as I was a Methodist. I was indebted to the Methodists, under God, for what little religion I had; being convinced that they were the people of God, I informed them that I could not be any thing else but a Methodist, as I was born and awakened under them, and I could go no further with them, for I was a Methodist, and would leave you in peace and love. I would do nothing to retard them in building a church as it was an extensive building, neither would I go out with a subscription paper until they were done going out with their subscription. I bought an old frame that had been formerly occupied as a blacksmith shop from Mr. Sims, and hauled it on the lot in Sixth near Lobard street, that had formerly been taken for the church of England. I employed carpenters to repair the old frame, and fit it for a place of worship . . .

. . . J— S— was appointed to take the charge in Philadelphia, he soon waked us up by demanding the keys and books of the church, and forbid us holding any meetings except orders from him; these propositions we told him we could not agree to. He observed he was elder appointed to the charge, and unless we submitted to him, he would read us all out of meeting. We told him the house was ours, we had bought it, and paid for it. He said he would let us know it was not ours, it belonged to the Conference; we took council on it; council informed us we had been taken in, according to the incorporation, it belonged to the white connection . . . About this time our colored friends in Baltimore were treated in a similar manner by the white preachers and Trustees, and many of them driven away; who were disposed to seek a place of worship, rather than go to law.

Many of the colored people in other places were in a situation nearly like those of Philadelphia and Baltimore, which induced us in April 1816 to call a general meeting, by way of Conference. Delegates from Baltimore and other places which met those of Philadelphia, and taking into consideration their grievances, and in order to secure the privileges, promote union and harmony among themselves, it was resolved, “That the people of Philadelphia, Baltimore, &c., &c., should become one body, under the name of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.”

Source: Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, The Life, Experience, and Gospel Labors of the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen: to Which Is Annexed, the Rise and Progress of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States of America: Containing a Narrative of the Yellow Fever in the Year of Our Lord 1793: with an Address to the People of Color in the United States (Philadelphia: F. Ford and M.A. Riply, 1880).

Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, The Life, Experience, and Gospel Labours of the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen, 1833

I was born in the year of our Lord 1760, on February 14th, a slave to Benjamin Chew, of Philadelphia. My mother and father and four children of us were sold into Delaware State, near Dover, and I was a child and lived with him until I was upwards of twenty years of age, during which time I was awakened and brought to see myself poor, wretched and undone, and without the mercy of God must be lost. Shortly after I obtained mercy through the blood of Christ, and was constrained to exhort my old companions to seek the Lord . . .

My master was an unconverted man, and all the family, but he was what the world called a good master. He was more like a father to his slaves than any thing else. He was a very tender, humane man . . . Our neighbours, seeing that our master indulged us with the privilege of attending meeting once in two weeks, said that Stokeley’s negroes would soon ruin him; and so my brother and myself held a council together that we would attend more faithfully to our master’s business, so that it should not be said that religion made us worse servants, we would work night and day to get our crops forward, so that they should be disappointed . . . So we always continued to keep our crops more forward than our neighbours, and we would attend public preaching once in two weeks, and class meeting once a week. At length our master said he was convinced that religion made slaves better and not worse, and often boasted of his slaves for their honesty and industry.

. . . I had it often impressed upon my mind that I should one day enjoy my freedom; for slavery is a bitter pill, notwithstanding we had a good master. But when we would think that our day’s work was never done, we often thought that after our master’s death we were liable to be sold to the highest bidder, as he was much in debt; and thus my troubles were increased, and I was often brought to weep between the porch and the altar. But I have had reason to bless my dear Lord that a door was opened unexpectedly for me to buy my time, and enjoy my liberty . . .

After peace was proclaimed I then travelled extensively, striving to preach the Gospel . . .

In 1793 a committee was appointed from the African Church to solicit me to be their minister, for there was no colored preacher in Philadelphia but myself.

Source: Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, The Life, Experience, and Gospel Labors of the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen: to Which Is Annexed, the Rise and Progress of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States of America: Containing a Narrative of the Yellow Fever in the Year of Our Lord 1793: with an Address to the People of Color in the United States (Philadelphia: F. Ford and M.A. Riply, 1880).

exhort – strongly encourage, urge

Background

Richard Allen was born a slave in Philadelphia, and when he was still a child, his mother and three siblings were sold away from him. Allen converted to Christianity after attending Methodist church meetings and began sharing the gospel with others. Eventually, Allen and his brother were given the opportunity to purchase their own freedom. This autobiography follows his life from his childhood through the establishment of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Transcript

Excerpts from Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, The Life, Experience, and Gospel Labours of the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen, 1833

I was born in the year of our Lord 1760, on February 14th, a slave to Benjamin Chew, of Philadelphia. My mother and father and four children of us were sold into Delaware State, near Dover, and I was a child and lived with him until I was upwards of twenty years of age, during which time I was awakened and brought to see myself poor, wretched and undone, and without the mercy of God must be lost. Shortly after I obtained mercy through the blood of Christ, and was constrained to exhort my old companions to seek the Lord. I went rejoicing for several days, and was happy in the Lord, in conversing with many old experienced Christians . . . I joined the Methodist society, and met in class at Benjamin Wells’s, in the forest, Delaware State . . .

My master was an unconverted man, and all the family, but he was what the world called a good master. He was more like a father to his slaves than any thing else. He was a very tender, humane man. My mother and father lived with him for many years. He was brought into difficulty, not being able to pay for us, and mother having several children after he had bought us, he sold my mother and three children. My mother sought the Lord and found favour with him, and became a very pious woman. There were three children of us remained with our old master. My oldest brother embraced religion and my sister. Our neighbours, seeing that our master indulged us with the privilege of attending meeting once in two weeks, said that Stokeley’s negroes would soon ruin him; and so my brother and myself held a council together that we would attend more faithfully to our master’s business, so that it should not be said that religion made us worse servants, we would work night and day to get our crops forward, so that they should be disappointed. We frequently went to meeting on every other Thursday; but if we were likely to be backward with our crops we would refrain from going to meeting. When our master found we were making no provision to go to meeting, he would frequently ask us if it was not our meeting day, and if we were not going. We would frequently tell him, “no, sir, we would rather stay at home and get our work done.” He would tell us, “Boys, I would rather you would go to your meeting: if I am not good myself, I like to see you striving yourselves to be good.” Our reply would be, “Thank you, sir; but we would rather stay and get our crops forward.” So we always continued to keep our crops more forward than our neighbours, and we would attend public preaching once in two weeks, and class meeting once a week. At length our master said he was convinced that religion made slaves better and not worse, and often boasted of his slaves for their honesty and industry. Some time after I asked him if I might ask the preachers to come and preach at his house. He being old and infirm, my master and mistress cheerfully agreed for me to ask some of the Methodist preachers to come and preach at his house. I asked him for a note. He replied, if my word was not sufficient, he should send no note. I accordingly asked the preacher. He seemed somewhat backward at first, as my master did not send a written request; but the class-leader (John Gray) observed that my word was sufficient; so he preached at my old master’s house on the next Wednesday. Preaching continued for some months; at length Freeborn Garrison preached from these words, “Thou art weighed in the balance, and art found wanting.” In pointing out and weighing the different characters, and among the rest weighed the slave-holders, my master believed himself to be one of that number, and after that he could not be satisfied to hold slaves, believing it to be wrong. And after that he proposed to me and my brother buying our times, to pay him sixty pounds gold and silver, or two thousand dollars continental money . . . I had it often impressed upon my mind that I should one day enjoy my freedom; for slavery is a bitter pill, notwithstanding we had a good master. But when we would think that our day’s work was never done, we often thought that after our master’s death we were liable to be sold to the highest bidder, as he was much in debt; and thus my troubles were increased, and I was often brought to weep between the porch and the altar. But I have had reason to bless my dear Lord that a door was opened unexpectedly for me to buy my time, and enjoy my liberty . . .

After peace was proclaimed I then travelled extensively, striving to preach the Gospel . . . In 1793 a committee was appointed from the African Church to solicit me to be their minister, for there was no colored preacher in Philadelphia but myself. I told them I could not accept of their offer, as I was a Methodist. I was indebted to the Methodists, under God, for what little religion I had; being convinced that they were the people of God, I informed them that I could not be any thing else but a Methodist, as I was born and awakened under them, and I could go no further with them, for I was a Methodist, and would leave you in peace and love. I would do nothing to retard them in building a church as it was an extensive building, neither would I go out with a subscription paper until they were done going out with their subscription. I bought an old frame that had been formerly occupied as a blacksmith shop from Mr. Sims, and hauled it on the lot in Sixth near Lobard street, that had formerly been taken for the church of England. I employed carpenters to repair the old frame, and fit it for a place of worship . . .

. . . J— S— was appointed to take the charge in Philadelphia, he soon waked us up by demanding the keys and books of the church, and forbid us holding any meetings except orders from him; these propositions we told him we could not agree to. He observed he was elder appointed to the charge, and unless we submitted to him, he would read us all out of meeting. We told him the house was ours, we had bought it, and paid for it. He said he would let us know it was not ours, it belonged to the Conference; we took council on it; council informed us we had been taken in, according to the incorporation, it belonged to the white connection . . . About this time our colored friends in Baltimore were treated in a similar manner by the white preachers and Trustees, and many of them driven away; who were disposed to seek a place of worship, rather than go to law.

Many of the colored people in other places were in a situation nearly like those of Philadelphia and Baltimore, which induced us in April 1816 to call a general meeting, by way of Conference. Delegates from Baltimore and other places which met those of Philadelphia, and taking into consideration their grievances, and in order to secure the privileges, promote union and harmony among themselves, it was resolved, “That the people of Philadelphia, Baltimore, &c., &c., should become one body, under the name of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.”

Source: Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, The Life, Experience, and Gospel Labors of the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen: to Which Is Annexed, the Rise and Progress of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States of America: Containing a Narrative of the Yellow Fever in the Year of Our Lord 1793: with an Address to the People of Color in the United States (Philadelphia: F. Ford and M.A. Riply, 1880).

Excerpt

Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, The Life, Experience, and Gospel Labours of the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen, 1833

I was born in the year of our Lord 1760, on February 14th, a slave to Benjamin Chew, of Philadelphia. My mother and father and four children of us were sold into Delaware State, near Dover, and I was a child and lived with him until I was upwards of twenty years of age, during which time I was awakened and brought to see myself poor, wretched and undone, and without the mercy of God must be lost. Shortly after I obtained mercy through the blood of Christ, and was constrained to exhort my old companions to seek the Lord . . .

My master was an unconverted man, and all the family, but he was what the world called a good master. He was more like a father to his slaves than any thing else. He was a very tender, humane man . . . Our neighbours, seeing that our master indulged us with the privilege of attending meeting once in two weeks, said that Stokeley’s negroes would soon ruin him; and so my brother and myself held a council together that we would attend more faithfully to our master’s business, so that it should not be said that religion made us worse servants, we would work night and day to get our crops forward, so that they should be disappointed . . . So we always continued to keep our crops more forward than our neighbours, and we would attend public preaching once in two weeks, and class meeting once a week. At length our master said he was convinced that religion made slaves better and not worse, and often boasted of his slaves for their honesty and industry.

. . . I had it often impressed upon my mind that I should one day enjoy my freedom; for slavery is a bitter pill, notwithstanding we had a good master. But when we would think that our day’s work was never done, we often thought that after our master’s death we were liable to be sold to the highest bidder, as he was much in debt; and thus my troubles were increased, and I was often brought to weep between the porch and the altar. But I have had reason to bless my dear Lord that a door was opened unexpectedly for me to buy my time, and enjoy my liberty . . .

After peace was proclaimed I then travelled extensively, striving to preach the Gospel . . .

In 1793 a committee was appointed from the African Church to solicit me to be their minister, for there was no colored preacher in Philadelphia but myself.

Source: Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, The Life, Experience, and Gospel Labors of the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen: to Which Is Annexed, the Rise and Progress of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States of America: Containing a Narrative of the Yellow Fever in the Year of Our Lord 1793: with an Address to the People of Color in the United States (Philadelphia: F. Ford and M.A. Riply, 1880).

exhort – strongly encourage, urge