Benjamin Franklin

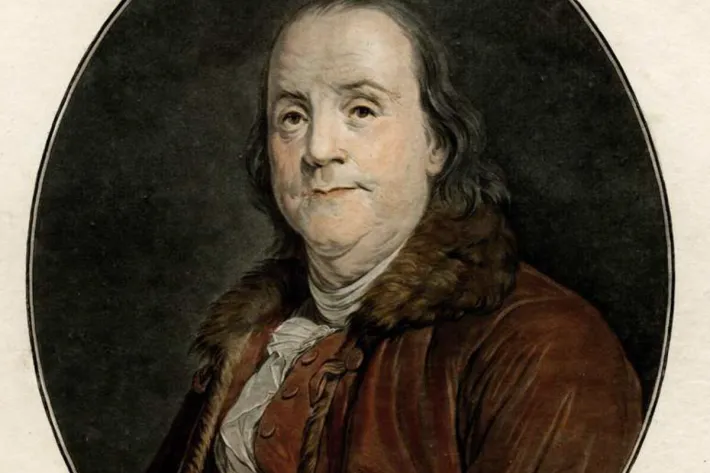

Benjamin Franklin, ca. 1789 (The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

Benjamin Franklin (1705–1790) was one of America’s first renaissance men—he was a statesman, scientist, writer, printer, and diplomat. Born in Boston, Franklin ran away at age 17 from an apprenticeship under his older brother. He eventually settled in Philadelphia and opened his own print shop. He published Poor Richard’s Almanack for twenty-five years and later wrote an autobiography that is still in print. His inventions, including the bifocal lens and the Franklin stove, as well as his investigations into the properties of lightning, earned him international recognition.

He spent most of the fifteen years before the Revolution in England representing Pennsylvania’s commercial and political interests. While he was away, his wife Deborah remained in Philadelphia to keep the printing business going. Devotion to individual freedom and love of his native land brought him back to America in 1775, drawn by the rumblings of independence in British North America. He was made a delegate to the Continental Congress, where he helped draft the Declaration of Independence and became one of its signers. A year later he was back across the Atlantic serving as the US minister to France, and signed both the French alliance with the US in 1778 and the Treaty of Paris ending the American Revolution in 1783.

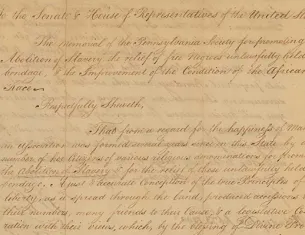

When Franklin returned from his position as minister to France in 1785 (passing the post on to Thomas Jefferson), he intended to retire from public service and devote himself to family life. Instead, he was elected president of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council, an equivalent position to today’s governor. He held the office until 1788. During this period, Franklin was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention and signed the US Constitution. He also agreed to serve as president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and submitted the first petition against slavery to the new US Congress.