Gouverneur Morris on the Liberty of France, 1789

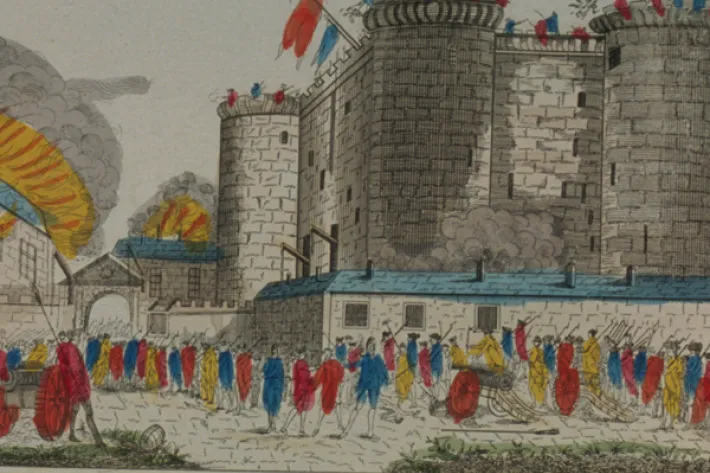

Citizens with guns and pikes outside of the Bastille, July 14, 1789 (Library of Congress)

Having witnessed one revolution, Gouverneur Morris was in a good position, as minister to France, to observe and comment on the rumblings for revolution in France in 1789. Just a few days before the first meeting of the Estates General since 1614, he described what was happening in France in great detail to the about-to-be inaugurated George Washington.

A Letter from Gouverneur Morris to George Washington, April 29, 1789

Paris 29 April 1789.

Dear Sir

I had the Pleasure to write to you a short Letter on the third of last Month. Monsieur de la fayette is since returned from his political Campaign in Auvergne, crowned with Success. He had to contend with the Prejudices and the Interests of his order, and with the Influence of the Queen and Princes (except the Duke of Orleans) but he was too able for his Opponents. He played the Orator with as much Eclat as he ever acted the Soldier, and is at this Moment as much envied and hated as his Heart could wish. He is also much beloved by the Nation, for he stands forward as one of the principal Champions for her Rights. The Elections are finished throughout this Kingdom, except in the Capital, and it appears from the Instructions given to the Representatives (called here les Cahiers) that certain Points are universally demanded which when granted and secured will render France perfectly free as to the Principles of the Constitution. I say the Principles, for one Generation at least will be required to render the Practice familiar. We have I think every Reason to wish that the Patriots may be successful. The generous Wish which a free People must form to disseminate Freedom, the grateful Emotion which rejoices in the Happiness of a Benefactor, and a strong personal Interest as well in the Liberty as in the Power of this Country, all conspire to make us far from indifferent Spectators. I say that we have an Interest in the Liberty of France. The Leaders here are our Friends, many of them have imbibed their Principles in America, and all have been fired by our Example. Their Opponents are by no Means rejoiced at the Success of our Revolution, and many of them are disposed to form Connections of the strictest Kind with Great Britain. The commercial Treaty emanated from such Dispositions; and according to the usual Course of those Events Which are shaped by human Wisdom, it will probably produce the exact Reverse of what was intended by the Projectors.

The Spirit of this Nation is at present high, and Mr Neckar is very popular; but if he continues long in Administration it will be somewhat wonderful. His Enemies are numerous able and inveterate. His Supporters are indifferent to his Fate, and will protect him no longer than while he can aid in establishing a Constitution. But When once that great Business is accomplished, he will be left to stand on his own Ground. The Court wish to get rid of him, and unless he shews very strong in the States General they will gratify their Wishes. His Ability as a Minister will be much contested in that Assembly, but with what Success Time only can determine. The Materials for a Revolution in this Country are very indifferent. Every Body agrees that there is an utter Prostration of Morals; but this general Position can never convey to an american Mind the Degree of Depravity.

It is not by any Figure of Rhetoric or Force of Language that the Idea can be communicated. A hundred Anecdotes and an hundred thousand Examples are required to shew the extreme Rottenness of every Member. There are Men and Women who are greatly and eminently virtuous. I have the Pleasure to number many in my own aquaintance: but they stand forward from a back Ground deeply and darkly shaded. It is however from such crumbling Matter that the great Edifice of Freedom is to be erected here. Perhaps like the Stratum of Rock which is spread under the whole Surface of their Country, it may harden when exposed to the Air; but it seems quite as likely that it will fall and crush the Builders. I own to you that I am not without such Apprehensions, for there is one fatal Principle which pervades all Ranks: It is a perfect Indifference to the Violation of Engagements. Inconstancy is so mingled in the Blood Marrow and very Essence of this People, that when a Man of high Rank and Importance laughs to Day at what he seriously asserted Yesterday, it is considered as in the natural order of things. Consistency is the Phenomenon. Judge then what would be the Value of an Association, should such a thing be proposed and even adopted. The great Mass of the common People have no Religion but their Priests, no Law but their Superiors, no Moral but their Interest. Those are the Creatures who led by drunken Curates are now in the high Road a la Liberté. And the first Use they make of it is to form Insurections every where for the Want of Bread. We have had a little Riot here Yesterday and the Day before, and I am told that some Men have been killed, but the Affair was so distant from the Quarter in which I reside that I know Nothing of the Particulars.

I am almost at the Bottom of my Paper without mentioning what I at first intended. Six Days ago I got from the Maker your Watch, with two Copper Keys and one golden one, and a Box containing a spare Spring and Glasses, all which I have delivered to Mr Jefferson who takes Charge of them for you. The Cost is 690 [Fr] leaving a Balle of [Fr] 32.12.2 which you will please to pay to Mr R. Morris, yours

Gouvr. Morris

Document Source: Library of Congress

A Letter from Gorverneur Morris to George Washington, April 29, 1789

Paris 29 April 1789.

Dear Sir

I had the Pleasure to write to you a short Letter on the third of last Month. Monsieur de la fayette is since returned from his political Campaign in Auvergne, crowned with Success . . . The Elections are finished throughout this Kingdom, except in the Capital . . . We have I think every Reason to wish that the Patriots may be successful. The generous Wish which a free People must form to disseminate Freedom, the grateful Emotion which rejoices in the Happiness of a Benefactor, and a strong personal Interest as well in the Liberty as in the Power of this Country, all conspire to make us far from indifferent Spectators. I say that we have an Interest in the Liberty of France. The Leaders here are our Friends, many of them have imbibed their Principles in America, and all have been fired by our Example . . .

. . . I own to you that I am not without such Apprehensions, . . . The great Mass of the common People have no Religion but their Priests, no Law but their Superiors, no Moral but their Interest. Those are the Creatures who led by drunken Curates are now in the high Road a la Liberté. And the first Use they make of it is to form Insurections every where for the Want of Bread. We have had a little Riot here Yesterday and the Day before, and I am told that some Men have been killed, but the Affair was so distant from the Quarter in which I reside that I know Nothing of the Particulars.

I am almost at the Bottom of my Paper without mentioning what I at first intended. Six Days ago I got from the Maker your Watch, with two Copper Keys and one golden one, and a Box containing a spare Spring and Glasses, all which I have delivered to Mr Jefferson who takes Charge of them for you. The Cost is 690 [₣] leaving a Balle of [₣] 32.12.2 which you will please to pay to Mr R. Morris, yours

Gouvr. Morris

Document Source: Library of Congress

Background

Having witnessed one revolution, Gouverneur Morris was in a good position, as minister to France, to observe and comment on the rumblings for revolution in France in 1789. Just a few days before the first meeting of the Estates General since 1614, he described what was happening in France in great detail to the about-to-be inaugurated George Washington.

Transcript

A Letter from Gouverneur Morris to George Washington, April 29, 1789

Paris 29 April 1789.

Dear Sir

I had the Pleasure to write to you a short Letter on the third of last Month. Monsieur de la fayette is since returned from his political Campaign in Auvergne, crowned with Success. He had to contend with the Prejudices and the Interests of his order, and with the Influence of the Queen and Princes (except the Duke of Orleans) but he was too able for his Opponents. He played the Orator with as much Eclat as he ever acted the Soldier, and is at this Moment as much envied and hated as his Heart could wish. He is also much beloved by the Nation, for he stands forward as one of the principal Champions for her Rights. The Elections are finished throughout this Kingdom, except in the Capital, and it appears from the Instructions given to the Representatives (called here les Cahiers) that certain Points are universally demanded which when granted and secured will render France perfectly free as to the Principles of the Constitution. I say the Principles, for one Generation at least will be required to render the Practice familiar. We have I think every Reason to wish that the Patriots may be successful. The generous Wish which a free People must form to disseminate Freedom, the grateful Emotion which rejoices in the Happiness of a Benefactor, and a strong personal Interest as well in the Liberty as in the Power of this Country, all conspire to make us far from indifferent Spectators. I say that we have an Interest in the Liberty of France. The Leaders here are our Friends, many of them have imbibed their Principles in America, and all have been fired by our Example. Their Opponents are by no Means rejoiced at the Success of our Revolution, and many of them are disposed to form Connections of the strictest Kind with Great Britain. The commercial Treaty emanated from such Dispositions; and according to the usual Course of those Events Which are shaped by human Wisdom, it will probably produce the exact Reverse of what was intended by the Projectors.

The Spirit of this Nation is at present high, and Mr Neckar is very popular; but if he continues long in Administration it will be somewhat wonderful. His Enemies are numerous able and inveterate. His Supporters are indifferent to his Fate, and will protect him no longer than while he can aid in establishing a Constitution. But When once that great Business is accomplished, he will be left to stand on his own Ground. The Court wish to get rid of him, and unless he shews very strong in the States General they will gratify their Wishes. His Ability as a Minister will be much contested in that Assembly, but with what Success Time only can determine. The Materials for a Revolution in this Country are very indifferent. Every Body agrees that there is an utter Prostration of Morals; but this general Position can never convey to an american Mind the Degree of Depravity.

It is not by any Figure of Rhetoric or Force of Language that the Idea can be communicated. A hundred Anecdotes and an hundred thousand Examples are required to shew the extreme Rottenness of every Member. There are Men and Women who are greatly and eminently virtuous. I have the Pleasure to number many in my own aquaintance: but they stand forward from a back Ground deeply and darkly shaded. It is however from such crumbling Matter that the great Edifice of Freedom is to be erected here. Perhaps like the Stratum of Rock which is spread under the whole Surface of their Country, it may harden when exposed to the Air; but it seems quite as likely that it will fall and crush the Builders. I own to you that I am not without such Apprehensions, for there is one fatal Principle which pervades all Ranks: It is a perfect Indifference to the Violation of Engagements. Inconstancy is so mingled in the Blood Marrow and very Essence of this People, that when a Man of high Rank and Importance laughs to Day at what he seriously asserted Yesterday, it is considered as in the natural order of things. Consistency is the Phenomenon. Judge then what would be the Value of an Association, should such a thing be proposed and even adopted. The great Mass of the common People have no Religion but their Priests, no Law but their Superiors, no Moral but their Interest. Those are the Creatures who led by drunken Curates are now in the high Road a la Liberté. And the first Use they make of it is to form Insurections every where for the Want of Bread. We have had a little Riot here Yesterday and the Day before, and I am told that some Men have been killed, but the Affair was so distant from the Quarter in which I reside that I know Nothing of the Particulars.

I am almost at the Bottom of my Paper without mentioning what I at first intended. Six Days ago I got from the Maker your Watch, with two Copper Keys and one golden one, and a Box containing a spare Spring and Glasses, all which I have delivered to Mr Jefferson who takes Charge of them for you. The Cost is 690 [Fr] leaving a Balle of [Fr] 32.12.2 which you will please to pay to Mr R. Morris, yours

Gouvr. Morris

Document Source: Library of Congress

Excerpt

A Letter from Gorverneur Morris to George Washington, April 29, 1789

Paris 29 April 1789.

Dear Sir

I had the Pleasure to write to you a short Letter on the third of last Month. Monsieur de la fayette is since returned from his political Campaign in Auvergne, crowned with Success . . . The Elections are finished throughout this Kingdom, except in the Capital . . . We have I think every Reason to wish that the Patriots may be successful. The generous Wish which a free People must form to disseminate Freedom, the grateful Emotion which rejoices in the Happiness of a Benefactor, and a strong personal Interest as well in the Liberty as in the Power of this Country, all conspire to make us far from indifferent Spectators. I say that we have an Interest in the Liberty of France. The Leaders here are our Friends, many of them have imbibed their Principles in America, and all have been fired by our Example . . .

. . . I own to you that I am not without such Apprehensions, . . . The great Mass of the common People have no Religion but their Priests, no Law but their Superiors, no Moral but their Interest. Those are the Creatures who led by drunken Curates are now in the high Road a la Liberté. And the first Use they make of it is to form Insurections every where for the Want of Bread. We have had a little Riot here Yesterday and the Day before, and I am told that some Men have been killed, but the Affair was so distant from the Quarter in which I reside that I know Nothing of the Particulars.

I am almost at the Bottom of my Paper without mentioning what I at first intended. Six Days ago I got from the Maker your Watch, with two Copper Keys and one golden one, and a Box containing a spare Spring and Glasses, all which I have delivered to Mr Jefferson who takes Charge of them for you. The Cost is 690 [₣] leaving a Balle of [₣] 32.12.2 which you will please to pay to Mr R. Morris, yours

Gouvr. Morris

Document Source: Library of Congress